November 5, 2009

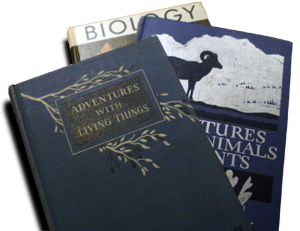

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

Authored by accomplished New York City educators Elsbeth Kroeber and Walter H. Wolff – she the sister of famed anthropologist Alfred Kroeber and he an intellectually ambitious department chair at DeWitt Clinton High School – Adventures (1938) delivered a solid corrective to the grossly anthropomorphic and depressingly deterministic textbooks of the 20s and 30s. It was one of the first of a wave of biology textbooks authored during the “Nazi years” that actively countered class and race prejudice and worked to undercut popular and institutional enthusiasm for eugenics. Other notable texts of this ilk include Smith’s Exploring Biology (also 1938) and Bayles and Burnett’s Biology for Better Living (1941).

ADVENTUROUS INDEED

Kroeber and Wolff’s brave book signaled its attack on the standard narrative and common conceits right from its opening pages.

Instead of the usual run of plants and animals from simplest to complex leading to “man,” the crown of creation and a creature apart, Adventures started with “man,” situated the species firmly within an interdependent biological space, and then moved with haste “down” through 150 pages of apes, reptiles, fishes, insects, invertebrates, to the “invisible” organisms and two brief chapters on plants on its way to the main body of the book, a nearly 500 page unit-based “unity of life” biology.

And as if that wasn’t enough, Kroeber and Wolff closed with another 150 pages on the “great generalizations of biology:” the unity of all living things, balance in nature, geological and organic change, the interplay of heredity and environment, evolution by the accumulation of very small changes, and finally, the potential of science to drive progress.

To understand how radical this was one need only compare Adventures With Living Things to the most popular textbooks at that time: Moon’s Biology, Smallwood’s New Biology, Baker and Mills’ Dynamic Biology and Curtis, Caldwell and Sherman’s Biology for Today. None of these texts devoted more than a few dozen pages to the “great generalizations.” All twisted and edited themselves to accommodate the concerns of textbook committees and school boards fearful of community objections to the teaching of reproduction and human evolution. Many contained startling race-based proofs of evolutionary “progress.” And all promoted eugenics without qualification. In fact, Moon’s text, which became Modern Biology in 1947, would continue to promote eugenics, calling it a “young science,” well into the 1960s.

However, Adventures With Living Things never gained much commercial traction. Though it was used in classrooms throughout New York City, no doubt because its authors had some influence there, it appears never to have generated much interest beyond the boroughs.

Why?

THE RAPIDLY EVOLVING LANDSCAPE

It is tempting to say Adventures With Living Things was unsuccessful because the book was simply too modern, too scientific, too evolutionary. It’s true that Adventures utterly ignored the unvoiced “rules” other authors and publishers followed in the years after Scopes – if you want to get your book past screening committees and school boards, don’t put the word ‘evolution’ in the index, substitute ‘change’ or ‘development’ for ‘evolution’ in the text, and make very sure you never state explicitly that humans evolved from ‘lower forms.’

Then again, Ella Thea Smith’s Exploring Biology didn’t follow those rules either. In fact, Smith’s publisher considered the fact that her text devoted more space to evolution than any other to be one of its key selling points.

Further, Smith took positions as strong and progressive as Adventures on the topics of race and eugenics.

Yet, over the next two and a half decades, Adventures With Living Things languished, while Exploring Biology went on to become the second most popular textbook in the country.

Adventures bigger problem in all probability was that it was simply too big. It came in at nearly 800 pages, and with its 3 dramatically different sections, was like 3 textbooks in one. Not until the BSCS textbooks of 1963 would the U.S. market see anything as non-traditional or academically demanding. The prep necessary to properly teach from the thing would have been daunting, and it would have taken a brave biology teacher to recommend its adoption.

THE STRUGGLE FOR EXISTENCE

Addressing this issue, the authors and publisher cut the book dramatically in 1948. The long introduction, the 157-page “reverse” phylogeny, was condensed into an introductory unit. The 200-page “great generalizations” section was cut out completely, its bits scattered throughout the remainder. The new, shorter, less adventurous book, re-titled Adventures With Animals And Plants, still contained a thorough accounting of theories of and evidences for evolution, and even greatly expanded its section on race based on Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish’s watershed pamphlet, “The Races of Mankind,” but now came in a more convenient tenth-grade size.

Unfortunately, by the time Kroeber and Wolff got their revision out, Ella Thea Smith had lapped them, and was coming up fast to do it again.

Smith tightened up Exploring Biology in 1943. She managed to insert a chapter on race based on Benedict and Weltfish’s pamphlet, even though it had been suppressed by the Army. Then in 1949, Smith revised her text yet again, this time including “a discussion of the emerging synthetic theory of evolution” (vi), which made it the first American textbook to do so. Smith also appended a new section on conservation which brought the text into line with the emerging national standard.

In a final desperate act, Adventures’ publisher D.C. Heath brought in a new writer, conservation scientist Richard L. Weaver, rebuilt the text’s units to match Smith’s, exactly, and reissued the book in 1957 under the simple and more grown up title, Biology.

As Biology, Kroeber, Wolff and Weaver’s text limped into the 60s. It finally failed in the face of the commercial market cataclysm that was the BSCS.

Sadly, Smith’s book failed too.

The only survivor, ironically, was that terrible monster, Modern Biology.

REFERENCES

I am most grateful to Dr. Robert Paul Wolff for sharing memories of his father with me via a short series of emails. Robert is the author of the very interesting blog, The Philosopher’s Stone, where he has (so far) posted 5 chapters of his memoir. Chapter One – Growing Up, along with Robert’s emails, provided much of the color of this article.

Kroeber, Elsbeth, Walter H. Wolff. 1938. Adventures With Living Things. Boston: D. C. Heath.

— 1948, 1950. Adventures With Animals And Plants. Boston: D. C. Heath.

Kroeber, Elsbeth, Walter H. Wolff, Richard L. Weaver. 1957. Biology Boston: D. C. Heath.

— 1965. Biology Boston: D. C. Heath.

lw6xr2