By 1940, biology’s core eugenics-based narrative had been dramatically weakened. Yet the demand for a curriculum that could control adolescent sexuality, had, if anything, only increased since the 1920s. Worries about what their sons and daughters were getting up to in the backseats of their new cars or in the sketchy motor courts popping up at the edge of town provided a fertile landscape for experimentation, even in a down market.

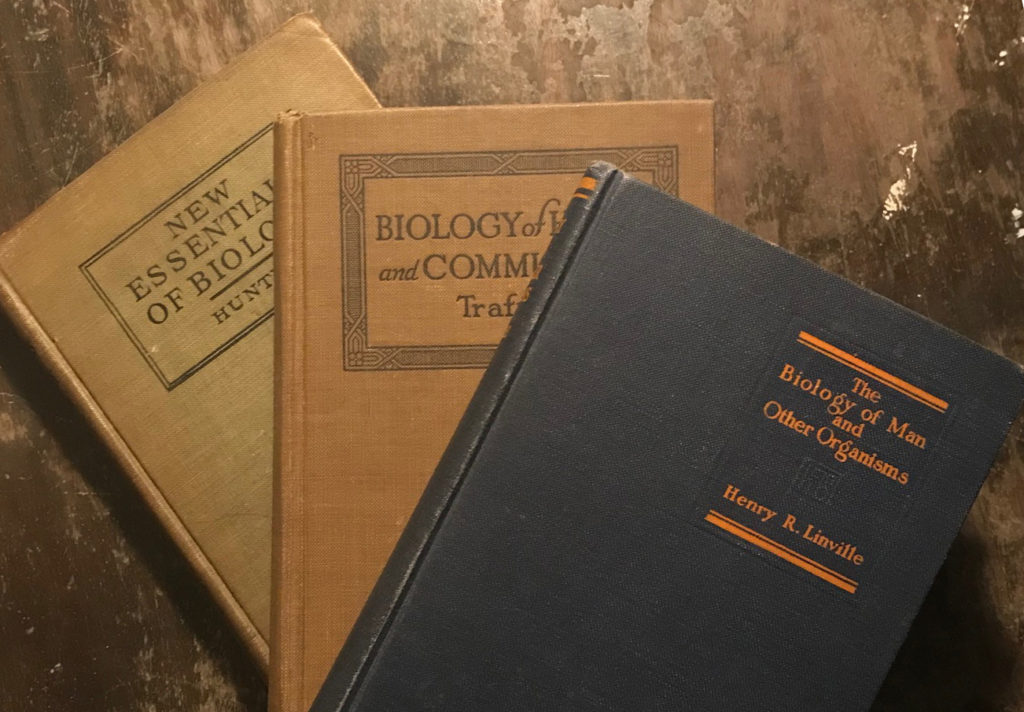

As of January 1, 2019, copyrighted works from 1923 are now in the public domain, including 3 important biology textbooks.

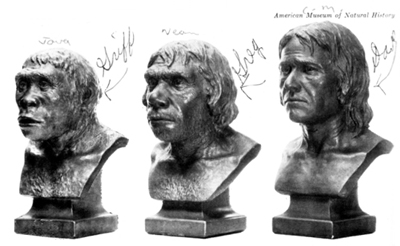

Piltdown man’s dramatic entry into textbooks starting in the mid-1930s was a reactionary effort by Henry Fairfield Osborn to infiltrate the debate on human origins and freeze in place his favored ideas of human evolution and the necessity of eugenic management. The success of his strategy is an American tragedy.

Piltdown man’s dramatic entry into textbooks starting in the mid-1930s was a reactionary effort by Henry Fairfield Osborn to infiltrate the debate on human origins and freeze in place his favored ideas of human evolution and the necessity of eugenic management. The success of his strategy is an American tragedy.

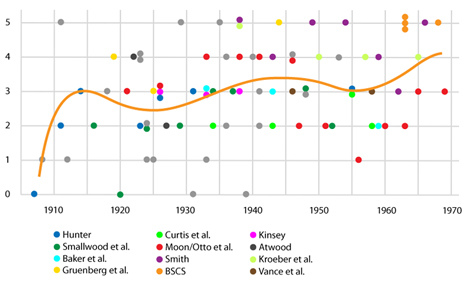

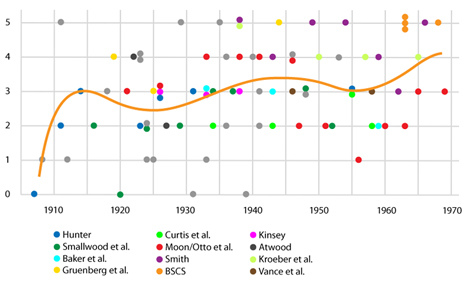

The relative priority of the topic of eugenics in the American biology curriculum graphed based on direct examination of 83 high school biology textbooks and 43 college-level biology textbooks published in the United States between 1904 and 1973. (Also see associated database).

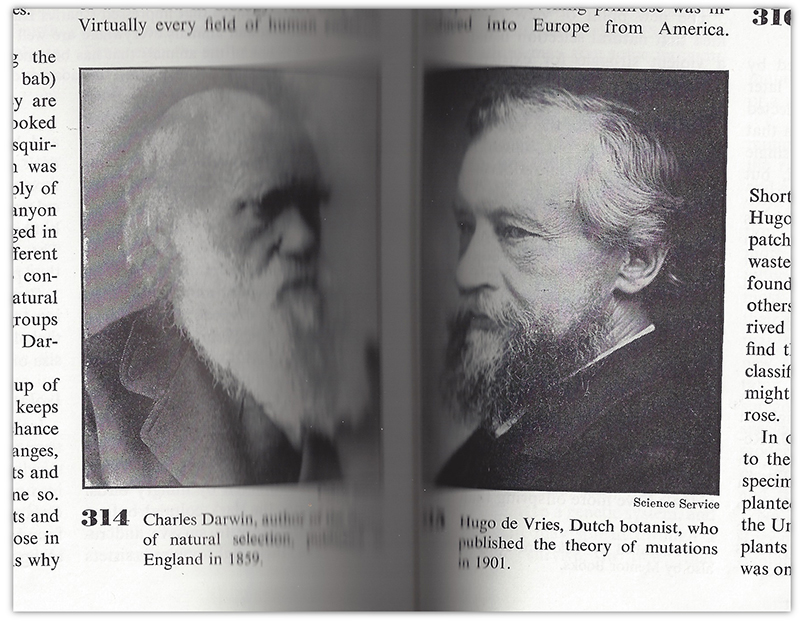

Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries gained global fame in the first decades of the twentieth century for being the guy who finally figured out how evolution worked. Today he is all but forgotten.  Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

Most of us think of conservation and ecology as more or less the same thing, with conservation the first step toward the restoration of an ecologically balanced state of nature. But through the first half of the twentieth century, the two words signified quite different things.

Samuel J. Holmes was a respected professor of zoology at Berkeley from 1912 until his death in 1964. He was also, and remained throughout his life, an unapologetic eugenicist.

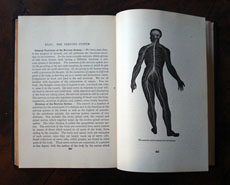

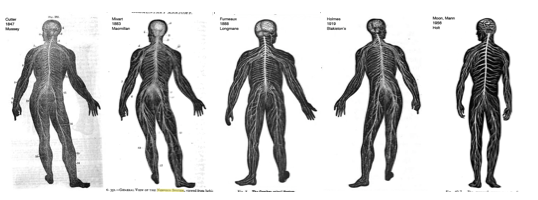

Tracing the history if a single illustration used in textbooks and popular anatomies throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries reveals surprising connections between the seemingly disparate topics of printing technology, print piracy, electricity, telegraphy, spirituality, abolition, and that most central of nineteenth century anxieties, masturbation.

Tracing the history if a single illustration used in textbooks and popular anatomies throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries reveals surprising connections between the seemingly disparate topics of printing technology, print piracy, electricity, telegraphy, spirituality, abolition, and that most central of nineteenth century anxieties, masturbation.

The “Nervous Icon” has mesmerized me for nearly three years (see Parts I, II and III).

“The Nervous Icon” is my name for an illustration of the human nervous system that found its way into dozens of anatomy, physiology and biology textbooks published between the mid-1800s and the mid-1900s. I began tracing its history in The Nervous Icon – Part I, where I touched on the issues of artistry, copyright, and mechanical reproduction in science textbooks. I followed up a month later in The Nervous Icon – Part II, where I went “over my head” into the history of encyclopedias and the tension caused by the conflict between the assumption that cultural artifacts were the property of the dominating imperialist power and the imperatives of the emerging global marketplace.

It remains striking how unwilling Harvard professor Calude Villee was to give up on eugenics …

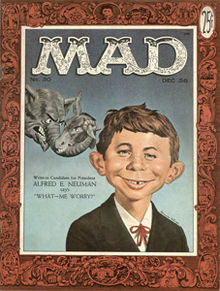

The big surprise for me was to learn that the image now universally known as Alfred E. Neuman was far from original to MAD.  In fact it had appeared throughout the twentieth century, often in association with variations of the phrase “Me worry?”, on postcards, print ads, calendars, business cards, enamel signs, buttons and perhaps even the nose of a World War II-era B-26 bomber.

In fact it had appeared throughout the twentieth century, often in association with variations of the phrase “Me worry?”, on postcards, print ads, calendars, business cards, enamel signs, buttons and perhaps even the nose of a World War II-era B-26 bomber.

A short article about the surprisingly long history of the topic of eugenics in American high school and college introductory biology textbooks.

A brief into to a new database of 38 college biology textbooks published in the United States between 1904 and 1964. Includes a chart tracking the relative priority of the topic of eugenics in the indexed texts.

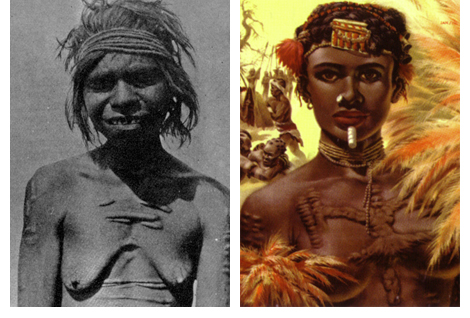

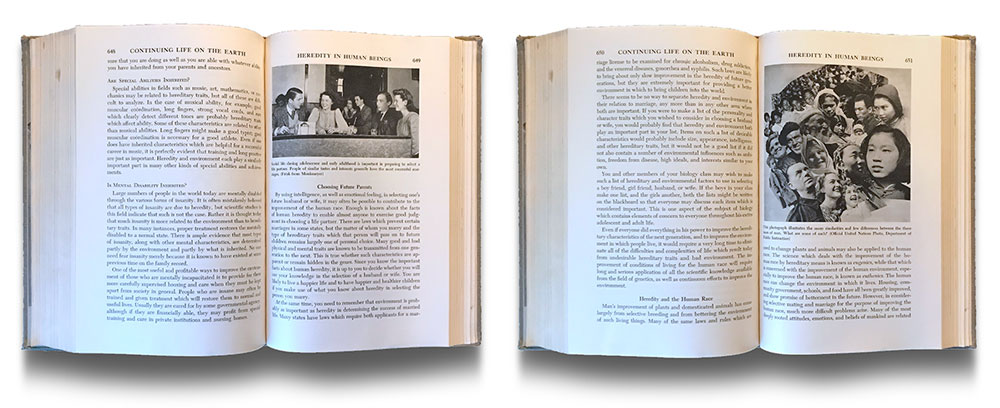

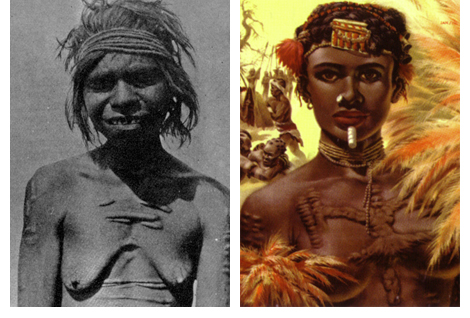

A weird thing happened in the years right after World War II: new college-level biology textbooks, rather than dropping the subject of eugenics, doubled down and began to defend the ideology with more aggressive rhetoric and moments of near-pornographic spectacle (WARNING: Disturbing photo).

Ellsworth Huntington had seen first hand the debilitating effects of the tropics on the bodies and morals of his fellow WASPs abroad, and literally feared luxuries like central heating were weakening his race at home.

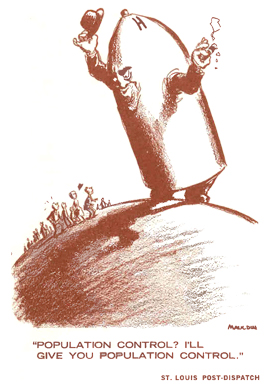

The “population bomb” was made as real and scary to school children in the 1960s as the H-bombs that drove them under their desks.

I’ve been playing around with the new Google Ngram Viewer … A few fast searches turned up some interesting correlations and relationships.

Another quick post ahead of longer article on pre- and post-WWII population rhetoric. This from Karl Sax, The Population Explosion, the November 1956 entry in the Foreign Policy Association’s well-regarded “Headline Series.”

Many of you are no doubt familiar with Paul Ehrlich’s bestseller, The Population Bomb, first published in 1968. Those of us of a certain age remember it sitting on the well-read suburban rebel’s bookshelf right between The Naked Ape and The Greening of America. But Ehrlich borrowed his title and thesis (with permission and acknowledgement) from these little books published by the Hugh Moore Fund.

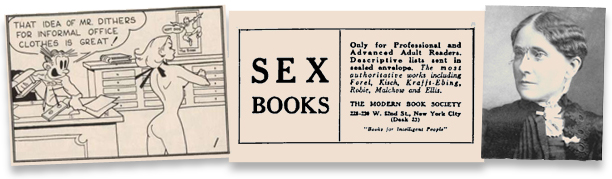

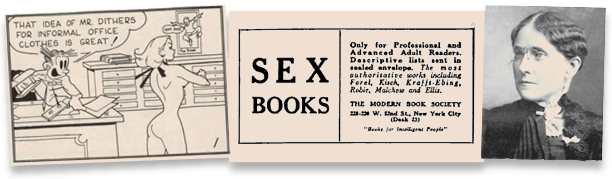

How pornographers exploited the topic of eugenics in the 1930s, and how in the process they undermined the puritanical authority of both America’s moral censors and its would-be managers of human reproduction. PART I | PART II

How pornographers exploited the topic of eugenics in the 1930s, and how in the process they undermined the puritanical authority of both America’s moral censors and its would-be managers of human reproduction. PART I | PART II

This article offers a brief discussion of sex and censorship in the United States, a short biography of birth control pioneer William J. Robinson, and a history of Joseph L. Lewis’ Eugenics Publishing Company.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring is considered by many the genesis event of the modern environmental movement. What is sometimes lost to our collective memory is that Silent Spring was a direct challenge to a long-dominant view of science as a progressive force

For most of the last 25 years, Howard M. Parshley, translator of the first English edition of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1953), has been cast as a saboteur of second-wave feminism.

The sculpted busts of “early man” by J. H. McGregor, and the paintings of Neanderthal flint workers and Cro-Magnon artists by Charles R. Knight, alchemized imaginary beasts of centuries past into icons of progress that carried the imprimatur of science. But the narrative they presented was conflicted from the start.

In this essay, I build on a dissertation by Donna J. Drucker on Alfred C. Kinsey, the famous sexologist, to see what a deep reading of the scientist’s high school textbook, An Introduction to Biology, might offer us in understanding both Kinsey the enthusiastic if overreaching entomologist, and Kinsey the groundbreaking if complexly motivated behavioral scientist.

An analysis of the relative priority of the topic of eugenics in the American high school biology curriculum based on review of 80 textbooks published between 1907 and 1969. Includes graph, database and notes.

Ronald L. Numbers has dedicated himself to this Sisyphean task of making sure we don’t commit the sin of relying on myths when doing history or promoting our worldview. A review of his latest book.

Ernst Haeckel’s embryos were a common fixture in a majority of high school and college biology textbooks from at least the mid-1930s on. Generations of students took away the incorrect but easy to accept and generally cool idea that we pass through a fish-like stage, complete with gill slits, on our way to becoming human. Article | Database

A database of 82 American high school biology textbooks. Includes observational notes and rankings relative to the topic of evolution.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Moon, Mann and Otto’s Modern Biology was the most popular biology textbook in the country, commanding upwards of 50% of the market. It was also among the most retrograde and out of date.

An analysis of the relative priority of the topic of evolution in high school textbooks between 1907 and 1969.

As we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, I thought I’d take the opportunity to note that the image of Darwin we share today, that tired looking but steadfast rock solid symbol of science, dates back only about 50, not 150 years.

After the Scopes, how many compromises were required to twist biology into something a conservative Tennessee or Texas textbook committee would approve?

Index and analysis of American high school biology textbooks published before 1923 now available via Google Books.

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

The image on the left is from a popular college textbook from the 1940s. The one on the right is from a Men’s Adventure magazine, otherwise known as a “sweat” or “armpit” pulp, from the 1950s.

In this article I suggest, despite their quite different contexts, these images served a common purpose.

Amram Scheinfeld’s 1939 You and Heredity was a bestseller, a hit not only with the general public, but also with life scientists.

Paul A. Lombardo’s history of Buck v. Bell, Three Generations, No Imbeciles, is a terrific telling of case of Carrie Buck, a young woman sterilized by Virginia in 1927.

After authoring Biology (1912), an innovative college level textbook, microbiologist and Wesleyan professor Herbert William Conn turned his attention to the grander task of subsuming eugenics within a broader and more social evolutionary ideology.

The 1930s were a time of remarkable innovation in the development of high school biology.

In its obituary, the Washington Post described Bentley Glass (1906-2005) as a “peripatetic figure in the 1950s and 1960s,” a man who seemed to be everywhere and advising everyone. In other obituaries Glass was described as “provocative” and “outspoken.” Editors of course made note of Glass’ more controversial comments, such as his 1971 statement that, “No parents will in that future time have the right to burden society with a malformed or mentally incompetent child,” a remark that the New York Times wrote, “is still regularly deplored by opponents of abortion.” Other notices, such as the one that appeared in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, labeled Glass more forgivingly as a “rabble-rouser,” and noted, “Of all his pronouncements, none permeated the cultural lexicon more than his 1962 prediction that cockroaches would be the sole survivors of nuclear war.”

In its obituary, the Washington Post described Bentley Glass (1906-2005) as a “peripatetic figure in the 1950s and 1960s,” a man who seemed to be everywhere and advising everyone. In other obituaries Glass was described as “provocative” and “outspoken.” Editors of course made note of Glass’ more controversial comments, such as his 1971 statement that, “No parents will in that future time have the right to burden society with a malformed or mentally incompetent child,” a remark that the New York Times wrote, “is still regularly deplored by opponents of abortion.” Other notices, such as the one that appeared in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, labeled Glass more forgivingly as a “rabble-rouser,” and noted, “Of all his pronouncements, none permeated the cultural lexicon more than his 1962 prediction that cockroaches would be the sole survivors of nuclear war.”

It came as a bit of a surprise to find that many American high school and college biology textbooks continued to discuss eugenics as if it were a non-controversial idea well into the rock-and-roll era.

The image in question is a stylized view of the human central nervous system. It appeared in what is arguably the very first modern American biology textbook, George W. Hunter’s 1907 Elements of Biology published by the American Book Company. This same image was copied, revised and republished repeatedly in textbooks into the 1960s.

The image in question is a stylized view of the human central nervous system. It appeared in what is arguably the very first modern American biology textbook, George W. Hunter’s 1907 Elements of Biology published by the American Book Company. This same image was copied, revised and republished repeatedly in textbooks into the 1960s.

A search on Abebooks turned up a 1949 Houghton Mifflin text I’d never heard of, The World of Life by Wolfgang F. Pauli. Curious, I ordered it.

Biology textbook authors in the first decades of the twentieth century helped undercut democracy and shore up the status quo by “confirming” suspicions that the “strongest” weren’t breeding, the “weakest” weren’t dying and that workers who did not know their genetically-determined place were a threat to the social order.

It is classical in pose and commands its stage. A black silhouette shot through with delicate white lines on a page dressed only with a pedestal-like caption that reads, “The central cerebro-spinal nervous system.”

Though Rachel Carson is usually credited for raising the public’s awareness of ecology, it was Marston Bates’ 1960 book, The Forest and the Sea, not Silent Spring, that made ecology a household word.

It’s a powerful symbol of capitulation: the straight on, serious portrait of Charles Darwin, the wizened, white bearded author of the Origin of Species and father of modern biology, was stripped from the frontispiece of a popular high school textbook, replaced by, of all things, a cartoon of the human digestive tract.

It’s a powerful symbol of capitulation: the straight on, serious portrait of Charles Darwin, the wizened, white bearded author of the Origin of Species and father of modern biology, was stripped from the frontispiece of a popular high school textbook, replaced by, of all things, a cartoon of the human digestive tract.

This excerpt from Kinsey’s text, Methods in Biology, provides an interesting glimpse into how a scientist in the 1930s counseled prospective teachers on how to navigate potential issues when handling the “related” topics of eugenics and evolution.

In his 1969 autobiography, An Adventure in Textbooks, Reid discussed how he helped Ella Thea Smith bring her homemade textbook, complete with its thorough discussion of the theory of evolution, to market in 1938.

Miller’s thesis is interesting as it was among the first papers to suggest that biology textbook authors and publishers progressively downplayed the theory of evolution in response to pressure from religious fundamentalists.

Downloadable PDF of Ella Thea Smith’s 1932 mimeographed and hand bound textbook.

Ella Thea Smith was the author of the second most popular high school biology textbook in the United States in the 1950s, Exploring Biology. At the height of its popularity it commanded roughly 25% of the market. Exploring Biology was first published in 1938, and was revised in 1943, ’49, ’54, ’59 and ’66. It featured many firsts.

After co-authoring the Mosaic web browser and co-founding and flipping Netscape, Marc Andreessen converted millions into billions though the investment firm Andreessen Horowitz. In that time, he also become a super-genius, consuming vast quantities of popular science and Ayn Rand-adjacent sociopathy and transmuting it into a power-justifying philosophy. Joining with Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and a host of other wealthy secondary-source thinkers, Andreessen, along with his TESCREAL brothers, believes a transhuman utopia, or, more accurately, a near utopia, is the destiny of our species, and that AI is our vehicle. But this will only happen, Andreessen warns, if progress is not limited by bureaucratic constraints, particularly those imposed by environmentalists. Oh, also only if smart people like himself start having more children.

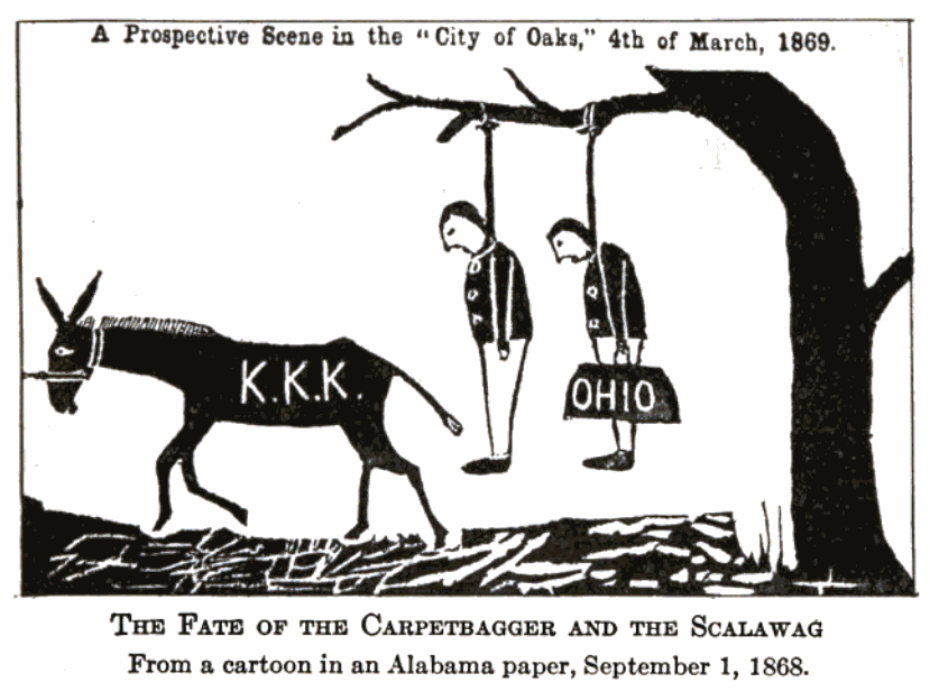

After co-authoring the Mosaic web browser and co-founding and flipping Netscape, Marc Andreessen converted millions into billions though the investment firm Andreessen Horowitz. In that time, he also become a super-genius, consuming vast quantities of popular science and Ayn Rand-adjacent sociopathy and transmuting it into a power-justifying philosophy. Joining with Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and a host of other wealthy secondary-source thinkers, Andreessen, along with his TESCREAL brothers, believes a transhuman utopia, or, more accurately, a near utopia, is the destiny of our species, and that AI is our vehicle. But this will only happen, Andreessen warns, if progress is not limited by bureaucratic constraints, particularly those imposed by environmentalists. Oh, also only if smart people like himself start having more children.  In the decades following Reconstruction, a decade-plus (1863-1877) effort by Congress to enfranchise and empower the 4,000,000 formerly enslaved people who resided in those states, American history textbooks, academic histories and popular histories constructed a narrative that provided white citizens absolution by positioning Reconstruction as a “tragic era” of “scalawags” and “ignorant negroes” manipulated by invaders from the North, “carpetbaggers,” who “swarmed” South after the Civil War to pillage and humiliate.

In the decades following Reconstruction, a decade-plus (1863-1877) effort by Congress to enfranchise and empower the 4,000,000 formerly enslaved people who resided in those states, American history textbooks, academic histories and popular histories constructed a narrative that provided white citizens absolution by positioning Reconstruction as a “tragic era” of “scalawags” and “ignorant negroes” manipulated by invaders from the North, “carpetbaggers,” who “swarmed” South after the Civil War to pillage and humiliate. To our Rachel Carson-tuned ears, the word conservation means allowing nature to hold sway, to designate areas as wetlands, protected habitats and forever wild, to be humble and accept that nature is usually smarter than we are. But to biology textbook authors in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, influenced by the eugenic ideas of Henry Fairfield Osborn, Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevelt and others, conservation meant something else entirely. It meant first, preserving select symbols of American virility, like the redwood tree, the bison, and most importantly, their own “great race,” and second, managing the rest of nature – forests, water resources, wildlife, and soil – so that it could be exploited maximally without collapse.

To our Rachel Carson-tuned ears, the word conservation means allowing nature to hold sway, to designate areas as wetlands, protected habitats and forever wild, to be humble and accept that nature is usually smarter than we are. But to biology textbook authors in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, influenced by the eugenic ideas of Henry Fairfield Osborn, Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevelt and others, conservation meant something else entirely. It meant first, preserving select symbols of American virility, like the redwood tree, the bison, and most importantly, their own “great race,” and second, managing the rest of nature – forests, water resources, wildlife, and soil – so that it could be exploited maximally without collapse. After a 96-year embargo (thanks,

After a 96-year embargo (thanks,  A visionary naturalist in the early 1940s on the order of Rachel Carson, by the 1960s, college biology professor Gairdner B. Moment devolved into a reactionary critic of the emerging culture of environmentalism he had helped spawn, and is remembered today as the scientist who wanted grizzly bears eliminated.

A visionary naturalist in the early 1940s on the order of Rachel Carson, by the 1960s, college biology professor Gairdner B. Moment devolved into a reactionary critic of the emerging culture of environmentalism he had helped spawn, and is remembered today as the scientist who wanted grizzly bears eliminated.

Piltdown man’s dramatic entry into textbooks starting in the mid-1930s was a reactionary effort by Henry Fairfield Osborn to infiltrate the debate on human origins and freeze in place his favored ideas of human evolution and the necessity of eugenic management.

Piltdown man’s dramatic entry into textbooks starting in the mid-1930s was a reactionary effort by Henry Fairfield Osborn to infiltrate the debate on human origins and freeze in place his favored ideas of human evolution and the necessity of eugenic management. Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries gained global fame in the first decades of the twentieth century for being the guy who finally figured out how evolution worked. Today he is all but forgotten. Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries gained global fame in the first decades of the twentieth century for being the guy who finally figured out how evolution worked. Today he is all but forgotten. Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them? Tracing the history if a single illustration used in textbooks and popular anatomies throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries reveals surprising connections between the seemingly disparate topics of printing technology, print piracy, electricity, telegraphy, spirituality, abolition, and that most central of nineteenth century anxieties, masturbation.

Tracing the history if a single illustration used in textbooks and popular anatomies throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries reveals surprising connections between the seemingly disparate topics of printing technology, print piracy, electricity, telegraphy, spirituality, abolition, and that most central of nineteenth century anxieties, masturbation.

How pornographers exploited the topic of eugenics in the 1930s, and how in the process they undermined the puritanical authority of both America’s moral censors and its would-be managers of human reproduction.

How pornographers exploited the topic of eugenics in the 1930s, and how in the process they undermined the puritanical authority of both America’s moral censors and its would-be managers of human reproduction.

In its obituary, the Washington Post described Bentley Glass (1906-2005) as a “peripatetic figure in the 1950s and 1960s,” a man who seemed to be everywhere and advising everyone. In other obituaries Glass was described as “provocative” and “outspoken.” Editors of course made note of Glass’ more controversial comments, such as his 1971 statement that, “No parents will in that future time have the right to burden society with a malformed or mentally incompetent child,” a remark that the New York Times wrote, “is still regularly deplored by opponents of abortion.” Other notices, such as the one that appeared in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, labeled Glass more forgivingly as a “rabble-rouser,” and noted, “Of all his pronouncements, none permeated the cultural lexicon more than his 1962 prediction that cockroaches would be the sole survivors of nuclear war.”

In its obituary, the Washington Post described Bentley Glass (1906-2005) as a “peripatetic figure in the 1950s and 1960s,” a man who seemed to be everywhere and advising everyone. In other obituaries Glass was described as “provocative” and “outspoken.” Editors of course made note of Glass’ more controversial comments, such as his 1971 statement that, “No parents will in that future time have the right to burden society with a malformed or mentally incompetent child,” a remark that the New York Times wrote, “is still regularly deplored by opponents of abortion.” Other notices, such as the one that appeared in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, labeled Glass more forgivingly as a “rabble-rouser,” and noted, “Of all his pronouncements, none permeated the cultural lexicon more than his 1962 prediction that cockroaches would be the sole survivors of nuclear war.” It’s a powerful symbol of capitulation: the straight on, serious portrait of Charles Darwin, the wizened, white bearded author of the Origin of Species and father of modern biology, was stripped from the frontispiece of a popular high school textbook, replaced by, of all things, a cartoon of the human digestive tract.

It’s a powerful symbol of capitulation: the straight on, serious portrait of Charles Darwin, the wizened, white bearded author of the Origin of Species and father of modern biology, was stripped from the frontispiece of a popular high school textbook, replaced by, of all things, a cartoon of the human digestive tract.