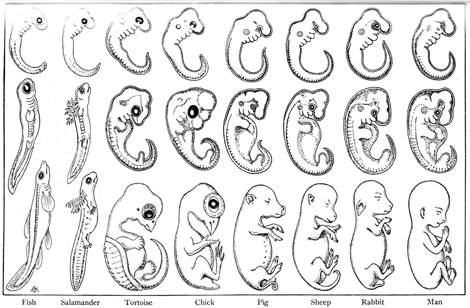

It is hard to deny that Haeckel’s embryos are an “icon of evolution,” true even if “icon” now evokes Jonathan Wells’ “travesty” of a book (see Matzke). The embryos were reproduced in a majority of high school and college biology textbooks from the mid-1930s through at least the 1960s (See table). Generations of students took away the incorrect but easy to accept and generally cool idea that we pass through a fish-like stage, complete with gill slits, on our way to becoming human.

Creationists, forever seeking advantage, took a 1997 journal article challenging the residual utility of Ernst Haeckel’s iconic embryos (Richardson et al.) and fashioned it into a pointy stick to poke their favorite straw man, the “scientific elite” (Pennisi, 1997; Behe, 1998; Wells, 1999; Freeman, 2001a,b; Ojala, 2004). With fresh charges of “fraud” and “fake,” these anti-evolutionists pricked a few scientists and historians. But the “prickees” fought back, and with context and nuance on their side, made quick work of the critics (Hopwood, 2006; Blackwell, 2007; Richards, 2009). Charges of fraud against Haeckel are as old as the drawings themselves, the defenders noted, just another out of date argument in the creationists’ pitiful quiver of half-truths and rhetorical manipulations.

Thrust. Parry.

But we must be careful: creationist attacks tend to generate simplified and emotional responses that can constrain critical thinking.

Haeckel’s “icon” was and remains a potent and problematic image (see Ken Miller and Joe Levine’s note). Though it is true that Haeckel’s “schematic” illustrations gave way to better representations starting in the late 1940s, biology textbooks continued to present embryos, always vertebrates, side-by-side or in a comparative grid. It’s an arrangement that was designed to communicate Haeckel’s belief that embryonic development and evolutionary history were linked and that evolution was progressive. It is easy to argue that it still does, despite the disclaimers authors usually offer.

What is most curious is that the rise in popularity of Haeckel’s embryos happened just as biologists were distancing themselves from the kind of broad morphologically-based conjecture the “icon” was designed to support. Less than 20% of early American biology textbooks (1907-1932) included all or part of Haeckel’s original grid. But by the 1940s and into the 1950s, upwards of 60% of high school textbooks featured copies or close variations of the 1874 original.

How do we explain this?

One explanation might be that biology textbooks, which are often authored by non-experts, are generally junk, always out of step and unrepresentative of the latest science. But not only is this not true, it does nothing to explain the increasing popularity of Haeckel’s drawings from the early to the middle of the twentieth century, nor the continued influence of his iconic scheme today.

Let’s dig a little deeper and see if we can find some real answers.

CONCEPTION

Haeckel’s embryos entered American biology textbooks not directly, but via a surrogate, George J. Romanes’ Darwin and after Darwin (published in 3 volumes between 1892 and 1898). Though Haeckel updated his array in 1891, it was the simple 8×3 grid from the 1874 edition of Anthropogenie, as copied by Romanes, that would serve as the template for nearly all versions published in the first half of the twentieth century.

Ironically, by the time Haeckel’s embryos appeared in an American textbook, Bigelow and Bigelow’s Applied Biology (1911), the “biogenetic law” the grid was created to illustrate – that the stage-by-stage development (ontogeny) of an embryo recapitulates its species’ evolutionary history (phylogeny) – was not just an anachronism, to a new generation of experimental biologists, it no longer qualified as science.

According to Garland Allen, the increasing focus on evidence-based research, exemplified by the work T. H. Morgan, was part of a generational “revolt from morphology.” Allen writes, “Controlled experimental conditions were seen by Morgan as providing the circumstances for detailed and quantitative analysis on limited, but answerable questions (Allen 67).

This might explain why Haeckel’s embryos were a relative rarity in the first three decades of the twentieth century. The grid appeared in just 3 of 26 high school and college textbooks published between 1907 and 1931.

However, it is likely more prosaic factors were at work as well.

As I discussed in “The Nervous Icon” (Part I, Part II), American publishers had tenuous and variable relationships with copyright law in the early years of the century. But after passage of the Copyright Act of 1909 publishers were careful not to simply lift art from competitors without permission or attribution. Generally.

And then there is the question of access and availability. Illustrations cost money to produce. Textbooks were (and are) a relatively low margin, and prior to the 1920s, low volume business. No doubt there was pressure to keep costs down. However, once an illustration was created, the house that paid for its creation could reuse it or even rent it out. Eventually “clear” copies multiply.

Haekel’s original illustration or Romanes’ copy, though uncredited, certainly served as the source for the developmental grid that appeared in Benjamin Gruenberg’s Elementary Biology (1919). The Gruenberg illustration in turn seems to have served as the source art for the grid as it appeared in Truman J. Moon’s revised Biology for Beginners (1933), though Moon credited his version to the American Museum of Natural History.

TAXONOMY

After Applied Biology, Haeckel’s embryo’s did not make their next appearance until they were retraced (with all figures flopped right) and reproduced in Benjamin Gruenberg’s 1919 Elementary Biology. Though the re-illustration carried no credit (Fig 1), it was clearly based on Haekel’s 1874 original. However, a slight mutation suggests just how “schematic” Haeckel’s originals were. The sixth embryo set in the series, Haeckel’s calf (rind in German) became a sheep in Gruenberg’s version. Later, in Everyday Biology (Curtis et al. 1943, 574), the same embryo set would magically become a dog.

The faithful Gruenberg variation represented only the second appearance of Haeckel’s full embryo set in a high school text. Though the complete 8×3 grid would appear in many college level texts throughout the century, the final embryo set in the series, that of “man,” would not appear again in high school textbooks until it was pulled from the grid and represented in a much less schematic style in Kroeber and Wolff’s 1948 Adventures with Animals and Plants (UPDATE: the full 8×3 grid appeared in Frank M. Wheat and Elizabeth T. Fitzpatrick’s 1929 Advanced Biology published by the American Book Company). Later, all three 1963 BSCS texts, the “blue,” “green” and “yellow” versions would include “man” in their modified series.

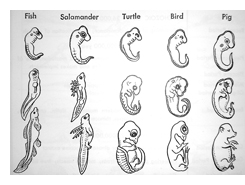

One additional variation source was William B. Scott’s 1917 Theory of Evolution. Used only in Woodruff’s college level Foundations of Biology (1922, 1923, 1927, 1930 and 1936), the drawing depicted a single stage (II) of 3 quite different looking embryos, fish (shark), bird and man.

Except for Woodruff’s use of Scott, Haeckel’s 1874 original served as soruce for all variations of the vertebrate grid reproduced in high school textbooks published between 1911 and 1962, with the exception of Kroeber and Wolff’s Adventures with Animals and Plants (1948, 1950), which was later revised and retitled Biology (1957). Interestingly, though the Gruenberg variation clearly served as the source of the version that appeared in all Moon textbooks (Biology for Beginners, Biology and Modern Biology) published by Holt between 1933 and 1965, the books carried a credit that read, “Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History.” It’s possible the museum acquired the rights to the image. But appropriation and “misattribution” of images was not an uncommon practice among publishers, particularly Holt.

DEVELOPMENT

How about this for irony? The first textbook, either at the high school or college level, to explicitly place Haeckel’s embryos in a section devoted to the topic of evolution was the much derided Biology for Beginners by Truman J. Moon (1933), the same textbook that dropped the use of the word evolution in favor of “racial development” (Fig. 2).

This poorly drawn 5×3 variation on Haeckel (by way of Gruenberg) appeared exactly as pictured here in all editions of Moon’s (et al.) popular textbook published between 1933 and 1965. Evidently without generating controversy.

Though earlier textbooks – Bigelow and Bigelow’s Applied Biology (1911), Gruenberg’s Elementary Biology (1919) and Atwood’s Civic and Economic Biology (1922) – presented the topic of evolution in a non-compromised pre-Scopes way, they did not use Haeckel’s grid to explicitly support acceptance of the theory of evolution. Instead the grid was deployed to illustrate a more general discussion of “development.” As they would throughout the century, “gill slits” (also called “gill-bars” and “gill arches”) centered the topic. Placed within the a discussion of development, Haeckel’s grid linked embryonic development with evolutionary development. The net effect was kind of a “recapitulation lite,” which could be forwarded but gently disclaimed. For example, both Gruenberg and Atwood were careful to caution against a literal application. Atwood stated, “the history is never perfectly repeated, and there are many short cuts and slight omissions” (19). Gruenberg, though he libelously referred to Haeckel’s theory as “Von Baer’s Law of Recapitulation” (Von Baer was famously critical of Haeckel), wrote, “strictly speaking, it is not true, for example, that you once passed though a hydra stage or a fish stage” (278). Later in the text, Gruenberg does refer back to his discussion of development as one point of evidence in support of evolution (467).

Moon’s inclusion of Haeckel’s grid in 1933 was part of his general expansion of the book’s section on evolution. In a chapter titled “The Facts of Racial Development Through the Ages,” Moon listed embryology along with fossils, homologous structures, vestigial organs, physiological similarities, environment, breeding, and experimentation (Hermann Muller’s experiments) all as evidence of evolution. The chapter following was dedicated to methods. It presented Larmarck’s acquired characteristics, Darwin’s natural selection and De Vries’ mutation theories as successive ideas. This presentation, though edited slightly and moved about, would remain virtually unchanged in Moon’s texts published through 1956.

The other high school texts published in the 1930s that included Haeckel’s grid – Curtis et al., Biology for Today 1934; Pieper et al., Everyday Problems in Biology 1936 – did not follow Moon’s lead in locking Haeckel’s embryos to a discussion of evolution. They instead linked the embryos to discussions of classification and reproduction. Not surprising for books published in the decade after Scopes. College texts however immediately picked up on, or at least paralleled, Moon’s lead. The first to do so, Rice’s An Introduction to Biology (1935), was remarkably Haeckelian. It linked taxonomy, ontogeny and phylogeny, and refereed to the “biogenetic law” with few disclaimers (506 – 513). The other contemporary college level texts that included the grid – Mavor’s General Biology (1936) and Stanford’s Man and the Living World were a little more modest in their presentation. Stanford wrote, “While the biolgenetic law – ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny – is not emphasized as much as it once was, it is still a useful generalization” (614).

One of the more interesting post-Haeckelian contextualizations of the gird occurred not in a college level text, as one might expect, but a remarkable (though evidentially not terribly popular) high school text, Downing and McAtee’s Living Things and You (1940). While virtually every biology textbook in the twentieth century discussed evolution relative to the evolution of animals (or just humans) alone, Downing and McAtee included evidence from botany. Using it made undercutting recapitulation easy. They wrote, “botanists never have been very enthusiastic supporters of the idea that development of the individual recapitulates the history of the race to which the individual belongs” (455).

The use of embryological illustrations in support of classification, development or evolution diversified greatly from 1940 on. Many textbooks at both the high school and college level begin to abandon Haeckel’s schematic drawings in favor of more accurate models (Parshley, 1940; Kroeber and Wolff, 1948; Brown, 1956; Villee, 1957). Others simply did not include any comparative vertebrate embryo drawings at all. And of those that did publish variations of Haeckel’s originals, most cautioned against the embrace of hard-line recapitulation. Karl Ernst Von Baer and his more general laws of embryological development were commonly mentioned to soften assumptions of recapitulation and salvage comparative embryology.

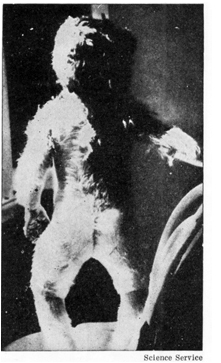

Fig. 3: Man and His Biological World (Jean et al. 1952) illustrated Haeckel’s “biogenetic law” not only with his grid of embryos, but with this photo of “the body of boy covered with hair” (411). This photo reinforced the idea that human embryos could get “stuck” before fully transitioning to a “completely evolved” modern form.

Smith’s generally up-to-date Exploring Biology, after ignoring Haekel through its first two editions (1938, 1943), half-heartedly presented Haeckel’s embryos in its 1949 and 1954 editions. Though the text always featured a strong presentation of the topic of evolution, only the 1954 edition coupled the drawings with that topic.

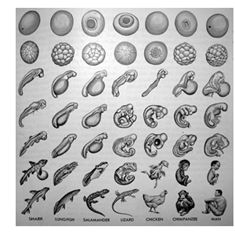

Fig. 4: The grid grew considerably in the 1963 BSCS “green” and “blue” versions. “Man” was restored after he had disappeared from high school textbooks published after 1919. Though the individual drawings are more accurate and feature strong variables like yolk sacs, the left to right, top to bottom scale-adjusted developmental grid remained fixed.

Haecekel’s grid was updated in the BSCS textbooks published in 1963 (Fig. 4). All three restored “man” to a grid that also featured more accurate and detailed embryo drawings. Though the authors “normalized” the embryos to make them all the same size (only the “green” version noted the scale shift), obvious pains were taken to illustrate the differences between each. While the “yellow” version continued to use its grid as evidence of evolution, the “green” and “blue” versions associated the gird with “development” and “adaptation” respectively. Of note: the “yellow” version broke from tradition by placing “man” not at the bottom right of the gird, but at the bottom left. The “yellow” version also mixed its 4 embryo sets – man, pig, salamander and chicken – countering the idea of evolutionary progress implied by Haeckel’s original.

CONCLUSION

As a rule, textbooks that traced their ancestry to editions published prior to 1938 had a hard time giving up on Haeckel and hard-line recapitulation. In one case, Moon’s series, the presentation of recapitulation coupled with Haeckel’s illustrations remained unchanged and unchallenged across the many editions published from 1933 into the 1960s.

It is interesting that the more scientifically up-to-date (and often less popular) books tended to include more sophisticated embryonic illustrations, or avoid comparing vertebrate embryos altogether. Those that did include variations on Haeckel’s gird generally did a good job of disclaiming or contextualizing recapitulation. In weaker, and unfortunately more “acceptable” books, like Modern Biology, Haeckel’s original grid was ironically more common.

The inclusion of Haeckel’s grid, minus “man,” in the perennially and preternaturally popular Moon series suggests that the image, badly drawn, represented the well-negotiated middle ground. It seems, despite their recent noise, creationists and their forebears cared little about this particular “icon of evolution” during its heyday. Embraced it even (Modern Biology was shamefully popular). The only textbooks they had trouble with were the better ones.

The author wishes to thank Nick Matzke for suggesting the topic of this article.

REFERENCES

For a complete list of textbooks surveyed, see the accompanying database

Allen, Garland. 1981 (1978). Life Sciences in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Behe, M. J. 1998. “Embryology and evolution.” Science 281:348.

Blackwell, W. H. 2001. “Don’t heckle Haeckel so much.” The American Biology Teacher 63:550-554.

Blackwell, W. H. 2007. “What to make of all this commentary on Haeckel.” The American Biology Teacher 69:135-136.

Freeman, B. 2001a. “The myth of the ‘biogenetic law.'” The American Biology Teacher 63:84.

Freeman, B. 2001b. “Haeckel’s forgeries.'” The American Biology Teacher 63:230.

Hopwood, Nick. 2006. “Pictures of evolution and charges of fraud: Ernst Haeckel’s embryological illustrations.” Isis 97:260-301.

Matzke, Nick. 2004. “Icon of Obfuscation: Jonathan Wells’s book Icons of Evolution and why most of what it teaches about evolution is wrong.” The TalkOrigins Archive (accessed December 24, 2009).

Pennisi, E. 1997. “Haeckel’s embryos: fraud rediscovered.” Science 277:1435.

Richards, Robert J. 2009. “Haeckel’s embryos: fraud not proven.” Biology and Philosophy 24:147-154.

Richardson, M. K., Hanken, J., Goodneratne, M. L., Pieau, C., Raynaud, A., Selwood, L., Wright, G. M. 1997. “There is no highly conserved embryonic stage in the vertebrates: implications for current theories of evolution and development.” Anatomy and Embryology 196:91-106.

Wells, J. 1999. “Haeckel’s embryos and evolution: setting the record straight.” The American Biology Teacher 61:345-349.

Wells, J. 2000. Icons of Evolution. Washington, DC: Regnery.

lg7vf6