July 3, 2009

I was not taught much of the history of eugenics in school, but I somehow absorbed that it was an “old” idea, one that had been thoroughly discredited once the horrors of the Nazis were exposed.

So it came as a bit of a surprise to find that many American high school and college biology textbooks continued to discuss eugenics as if it were a non-controversial idea well into the rock-and-roll era. In fact, the most popular textbook published in 1960, Moon, Otto and Towle’s Modern Biology, referred to eugenics as “a young science,” (648) and suggested its methods would surely begin to see application once a few more properly studied human generations had passed.

So it came as a bit of a surprise to find that many American high school and college biology textbooks continued to discuss eugenics as if it were a non-controversial idea well into the rock-and-roll era. In fact, the most popular textbook published in 1960, Moon, Otto and Towle’s Modern Biology, referred to eugenics as “a young science,” (648) and suggested its methods would surely begin to see application once a few more properly studied human generations had passed.

Yes, Modern Biology was always a bit behind the times. But when it came to eugenics, it wasn’t behind by that many years.

Though a few popular textbook authors began to challenge the assumptions of eugenicists starting in the late 1930s (Smith, 1938) and then significantly downplay or drop the topic entirely starting in the 1940s (Gruenberg and Bingham, 1944), most continued to repeat, in only slightly abridged form, the same claims of eugenic necessity and urgency advanced in the 1920s and 1930s.

Rand McNally’s Dynamic Biology series – Dynamic Biology (1933), Dynamic Biology Today (1943) and New Dynamic Biology (1959) – provides an illustrative example of the history of the idea of eugenics in American high school textbooks. A comparison of these texts not only demonstrates the continued affection authors held for the idea of eugenics, but, when one looks carefully, hints strongly at what finally forced authors to abandon explicit promotion of the topic.

DYNAMIC BIOLOGY: THE TEXT

Arthur O. Baker and Lewis H. Mills 1933, Dynamic Biology represented a breakthrough. It was one of the first high school textbooks to adopt a construction that had become common in college level textbooks which linked chapters on reproduction, heredity, biological improvement and evolution together to tell a sweeping story of progress. The narrative proved powerful enough to establish itself, like the QWERTY keyboard, as a lock-in. Most competing textbooks adopted a near identical structure. Those that didn’t failed in the marketplace.

But demonstrating that it is not always good to be the first to market, Dynamic Biology, though it was popular enough to warrant a reprint in 1938, a new edition (Dynamic Biology Today) in 1943, and subsequent reprints in 1947 and 1948, appears not to have competed well against Modern Biology, the most popular textbook at the time, or Exploring Biology, the emerging contender. The 1959 edition, titled New Dynamic Biology, seems to have been a last gasp effort on the part of Rand McNally to revive the title. Its rarity in the used book market suggests the effort was a failure. Rand McNally would abandon the title and contract with the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study to publish the hugely popular BSCS Green Version in 1963, ironically, the first biology textbook to gain success without following the basic structure established by Dynamic Biology in 1933.

A comparison of the text of the major editions of the series underscores the stability of the progress-oriented argument first presented in Dynamic Biology, an argument for which eugenics served as a capstone. A comparison of the references section appended to the text proper highlights both the hardcore nature of textbook eugenics in the 1930s and the increasingly difficult challenge proponents faced accommodating shifting ideologies and rapid cultural change at the dawn of the 1960s.

Let’s look at the text first.

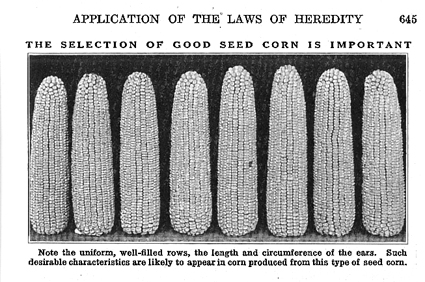

Corn was an all purpose metaphor in biology textbooks of the twentieth century. The photo used in Baker and Mills’ book of 8 standing ears, all tall, uniform and white, illustrated “the value of selection” (644), and served as an introduction to how “Mendel’s Laws” could be applied to plant, animal and human improvement.

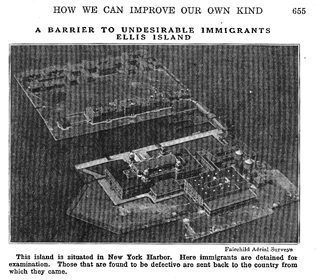

Baker and Mills introduced eugenics, its necessity and potential, by comparing (as many authors did) the generational lines of the Kallikak (see also) and Edwards families (like eugenics, the Kallikak/Edwards comparison survived into the 1950s). Baker and Mills used the Kallikak study to warn of the dangers of indiscriminate breeding, but suggested these dangers could be mitigated by sex education, careful mate selection and a policy of restrictive immigration.

Dynamic Biology (1933), pp. 648-659.

Improvement by heredity. The secret of improving the human species lies in an improvement of the human stock. In other words, it requires purification of stock to make more certain the transmission of favorable genes. The following measures will help.

- All the intelligent members of society should become acquainted with the laws of heredity.

- So far as possible the feeble-minded, criminal, and degenerate should be prevented from reproducing their kind.

- Marriage between members of families of good mental and physical characteristics should be encouraged.

- Immigrants of defective stock should not be admitted to our country.

- Good physical and mental health should be maintained. This means that we should ever strive to be physically fit and maintain a cheerful and hopeful outlook on life.

In 1943, Baker and Mills moderated their language, slightly. For example, “purification” became “improvement.” And students were given a role, instructed that they could make a positive impact on the genetic health of the nation not only by supporting government policy, but also by chosing their mates wisely.  A photo of Ellis Island still decorated the page, as it had in 1933, reminding students of the danger of genetic invasion.

A photo of Ellis Island still decorated the page, as it had in 1933, reminding students of the danger of genetic invasion.

Dynamic Biology Today (1943), pp. 608-617.

Improvement by heredity.

The secret of improving the human species lies in an improvement of the human stock. In other words, it requires purification of stockHuman beings have no pedigrees which compare with those of domestic animals. The secret of improving the human species, however, lies in the improvement of human stock. It requires improvement of stock to make more certain the transmission of favorable genes. The following measures will help:

- All the intelligent members of society should become acquainted with the laws of heredity.

- So far as possible the feeble-minded, criminal, and degenerate should be prevented from reproducing their kind.

- Marriage between members of families of good mental and physical characteristics should be encouraged. Each individual contemplating marriage should consider carefully whether the resulting combination of family characteristics and traits would be likely to produce desirable offspring.

- Immigrants

of defective stock should not be admitted to our countryshould be carefully examined for physical and mental weaknesses, and admission should be denied to those of defective stock.- Good physical and mental health should be maintained. This means that we should ever strive to be physically fit and maintain a cheerful and hopeful outlook on life.

Changes to the text in the 1959 edition, specifically the inclusion of the phrase “percentage and transmission of favorable genes in the populations of the world,” as well as the elimination of the bullet point on immigration, suggest both a marginal familiarity with the more population-oriented perspective of the modern synthesis and an awareness that eugenics, if it were to be promoted at all, had to be reframed in less nationalistic terms.

New Dynamic Biology (1959), pp. 417-425.

Improvement by heredity. Human beings have no pedigrees which compare with those of domestic animals. The secret of improving the human species, however, lies in the improvement of human stock.

It requires improvement of stock to make more certain the transmission of favorable genes. The following measures will helpImprovement of the hereditary quality of mankind depends upon efforts to increase the percentage and transmission of favorable genes in the populations of the world. Such efforts should include the following measures:

- All intelligent members of society

should become acquainted with the laws of heredity.– but especially young people – should learn the laws of heredity and how they operate.- So far as possible the feeble-minded, criminal, and degenerate should be prevented from reproducing their kind.

- Marriage between members of families of good mental and physical characteristics should be encouraged. Each individual contemplating marriage should consider carefully whether the resulting combination of family characteristics and traits would be likely to produce desirable offspring.

Immigrants should be carefully examined for physical and mental weaknesses, and admission should be denied to those of defective stock.- Good physical and mental health should be maintained. This means that we should ever strive to be physically fit and maintain a cheerful and hopeful outlook on life.

By the standards of the 1930s, Baker and Mills original text is hardly noteworthy. Eugenics, as a scientific solution to the social problems of poverty and criminality, first introduced into the biology curriculum in Hunter’s A Civic Biology (1914), had been promoted in almost all the most popular textbooks (Hodge and Dawson, Moon, Atwood, Peabody and Hunt, Smallwood, and even Gruenberg) through the 1920s and into the 1930s as both a necessity and a no-brainer. The dollars being spent on “environmental improvement,” which Smallwood in New Biology (1937) tallied at exactly $1,385,220,000 over the previous 23 years, was positioned as so much money going down the drain if an equal effort was not made to improve “hereditary history” (394).

However, by its 1943 edition, Baker and Mills’ book had already begun to fall out of step. Smith in Exploring Biology (1938) and Bayles and Burnett in Biology for Better Living (1941), introduced the topic of eugenics mostly in order to undercut its claims. Later, Vance and Miller’s Biology for You (1946) gave but one line to eugenics, and cut that line in the 1958 revision.

But as evidenced by Wolfgang F. Pauli’s The World of Life (see article), biologists were loath to simply delete from their texts one of their main claims to social relevance, particularly at a time when biology, never a confident science, was seeing its status further diminished relative to the celebrated industrial and military successes of chemistry and physics. This, along with the militarized and rationalized culture of the Cold War, catalyzed by the launch of Sputnik in 1957, encouraged biologists to swing for the fences, exploit growing fears of a human “population bomb” and promote their science as the most important because it served as an essential interface between the cold facts of reductionism and the hard realities of social policy.

But by the end of the 1950s, biologists faced a terrible problem. The ideology of linked biological and cultural progress, central to the science’s claims, was built upon two pillars that had gone shaky: the claim that evolution was naturally progressive and the claim that the “doctrine of evolution” applied to both physical and cultural development. Further, in the years after Brown v. Board of Education, race, which had through the 30s served as an uncontroversial measure of physical and cultural progress, now somehow wasn’t real, wasn’t obvious or didn’t matter.

Try as they might, Baker and Mills, along with many other reform eugenicists, including geneticist and BSCS chairman Bentley Glass, could not reconcile the contradictions. Though anthropologist Ashley Montagu had argued since 1942 that race was a cultural construct, biologists could not go so far. Instead, they argued that race was real, but that the color of one’s skin did not define a race’s borders. Race was a genotypic, not a phenotypic phenomena. And only the scientist should judge.

This argument, though clever, would ultimately prove inadequate.

As shown above, only minor changes were made to the text of the Dynamic Biology series between 1933 and 1959. That makes the changes to the references all the more interesting and revealing.

DYNAMIC BIOLOGY: THE REFERENCES

In 1933, the books listed in Dynamic Biology’s reference section reinforced the basic notion that the supposedly progressive power of natural selection had been undermined by medical and cultural advances, and that it was critical scientists be given authority to set standards and guide reproduction in the industrial future.

Thanks to Google, several of these books are available online.

1933

- Rice, Thurman B. 1927. Racial Hygiene.

- Downing, Elliot R. 1928. Elementary Eugenics, a revision to Downing’s 1918 The Third and Fourth Generation.

- Jewett, Frances Gulick. 1914. The Next Generation.

- Wiggam, Albert Edward. 1924. The Fruit of the Family Tree.

- Various encyclopedia entries and popular science articles on inheritance and eugenics.

The 1943 list exposes the cracks that had begun to develop in the premises of eugenicists. Of note is the inclusion of Amram Scheinfeld’s popular 1939 book, You and Heredity, after the more typical eugenic fare (including the incredibly frightening Tomorrow’s Children, credited to, but probably only compiled by, climatic determinist Ellsworth Huntington). Though not a scientist himself, Scheinfeld’s work was extremely well reviewed in the journals, embraced not only for its accuracy, but because it seemed to offer a path around the cultural roadblocks eugenically oriented geneticists were beginning to encounter.

Along with Frederick Osborn’s Preface to Eugenics (1940), Scheinfeld’s book would serve as the backbone of the intellectual argument Daniel Kevles has labeled “reform eugenics.”

1943

- Davenport, Charles B. 1936. How We Came by Our Bodies.

- Guttmacher, Alan F. and Rosa Kohn. 1933. Life in the Making.

- Huntington, Ellsworth and Others. 1935. Tomorrow’s Children.

- Newman, Horatio Hackett. 1940. Multiple Human Births.

- Scheinfeld, Amram. 1939. You and Heredity.

- Waddington, Conrad H. 1936. How Animals Develop.

- Encyclopedia entries on inheritance, heredity and environment.

The 1959 list is the most revealing. Though few changes were made to the preceding text, all “old school” eugenic references were eliminated. In their place were the “reform” books of Scheinfeld and Osborn, plus, critically, two documents one can assume the textbook’s authors hoped would mitigate any accusation of prejudice in the eugenic argument: Boyd and Asimov’s (misspelled ‘Asimon’ in the list) Races and Peoples and Montagu’s Statement on Race, which served as the foundation for the United Nation’s statement on race.

1959

- Boyd, William C. and Isaac Asimon (sic). 1955. Races and Peoples.

- Duvall, Evelyn Millis. 1950. Family Living.

- Montagu, Ashley. 1951. Statement on Race.

- Osborn, Frederick. 1940. Preface to Eugenics.

- Scheinfeld, Amram. 1950. The New You and Heredity.

- Stanford, E. E. 1951. Man and the Living World.

- Encyclopedia entries on Mendel and Darwin, heredity and environment.

Kevles states that during the teens and 1920s, “the science of human biological improvement provided an avenue to public standing and usefulness” for biologists (69). However, for all of its early “promise,” by the 1930s eugenics was proving itself a dry well for research. As Phillip Pauly writes, “Biologists left eugenics less because of refutation or revulsion than from a dearth of innovation” (Pauly, 2000, 216). Further, eugenics became increasingly identified with racists and nativists. Reform eugenics was a clever attempt to sidestep race and class issues; to allow for the support of liberal economic policies while retaining the claims to authority and purpose that were so clear to life scientists just a couple of decades before.

Textbook authors, though often less careful in their language and argument than public research scientists, were not as far out of step or disconnected from the latest thinking in their field as we might today wish to think.

What this examination shows is that many biologists still held out hope that eugenics could be reconciled with liberalized social and cultural attitudes through the 1950s. But despite the best efforts of well-meaning people like Bentley Glass, eugenics could not survive side-by-side with ideologies that promoted racial, class and/or gender equality.

REFERENCES

Atwood, Wm. H. 1922. Civic and Economic Biology. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co.

Baker, Arthur O., Lewis H. Mills. 1933. Dynamic Biology. New York: Rand McNally & Company.

–. 1943. Dynamic Biology Today. New York: Rand McNally & Company.

Baker, Arthur O., Lewis H. Mills., Julius Tanczos Jr. 1959. New Dynamic Biology. New York: Rand McNally & Company.

BSCS. 1963. (“blue” version) Biological Science: Molecules to Man. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company.

–. 1963. (“green” version) High School Biology. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company.

–. 1963. (“yellow” version) Biological Sciences: An Inquiry into Life. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Glass, Bentley. 1962. “Renascent Biology: A Report on the AIBS Biological Sciences

Curriculum Study.” The School Review 70: 16-43.

Gruenberg, Benjamin C. 1925. Biology and Human Life. Boston: Ginn and Company.

Hodge, Clifton F., Jean Dawson. 1918. Civic Biology. Boston: Ginn and Company.

Kevles, Daniel J 1985. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Montagu, Ashley. 1942. Man’s Most Dangerous Myth. New York: Columbia University Press.

Moon, Truman J., Paul B. Mann, James H. Otto. 1956. Modern Biology. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

–. 1947. Modern Biology. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Moon, Truman J., James H. Otto, Albert Towle. 1960. Modern Biology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Pauly, Philip J. 2000. Biologists and the Promise of American Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

–. 1991. “The Development of High School Biology: New York City, 1900–1925.” Isis 82.

Peabody, James Edward, Arthur Ellsworth Hunt. 1929. Biology and Human Welfare. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Selden, Steven. 1999. Inheriting Shame: The Story of Eugenics and Racism in America. New York: Teachers College Press.

Smallwood, W. M., Ida L. Reveley, Guy A. Bailey. 1937. New Biology Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Smith, Ella Thea. 1959. Exploring Biology: Fifth Edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

–. 1942. Exploring Biology: New Edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

–. 1938. Exploring Biology. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Vance, B. B. 1946. Biology for You. Chicago: J. B. Lippincott Company.

–. 1958. Biology for You. Chicago: J. B. Lippincott Company.

The title of this post intentionally echoes Don McLean’s 1972 hit, “American Pie,” a song about the February 1959 plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and “The Big Bopper.” Though perhaps too cute a title for such a serious topic, I couldn’t resist using it given the coincidental timing.

Fascinating material!!! Thank you!!!

ppqzu5