March 22, 2009

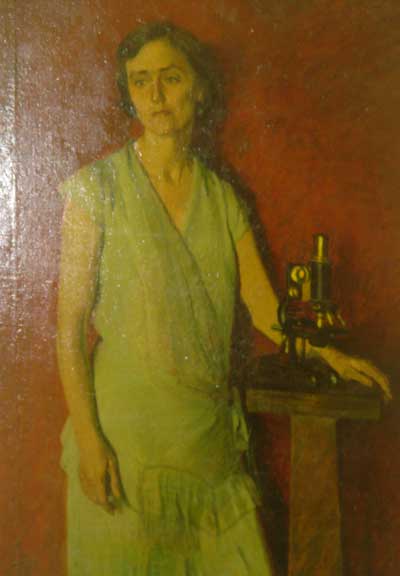

Ella Thea Smith was the author of the second most popular high school biology textbook in the United States in the 1950s, Exploring Biology. At the height of its popularity it commanded roughly 25% of the market. Exploring Biology was first published in 1938, and was revised in 1943, ’49, ’54, ’59 and ’66. It featured many firsts.

Ella Thea Smith was the author of the second most popular high school biology textbook in the United States in the 1950s, Exploring Biology. At the height of its popularity it commanded roughly 25% of the market. Exploring Biology was first published in 1938, and was revised in 1943, ’49, ’54, ’59 and ’66. It featured many firsts.

The 1938 edition featured extensive treatments of the topics of human evolution and reproduction. Though her publisher expected the book to do poorly in the south, it was approved for use in the Atlanta (GA) school district as well as many other areas in the country. By the 1960s her textbook was in use in every state.

The 1943 edition featured a comprehensive section on race based on Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish’s “The Races of Mankind,” a pamphlet that was commissioned, produced, but then “notoriously” suppressed by the US Army. Interestingly, Smith’s ’43 text, with its section on race intact, was reprinted under paper cover for use by the US Marines in 1945.

The ’49 edition of Exploring Biology was the first American textbook to feature a discussion of the modern synthesis, reflecting the influence of one of Smith’s readers, paleontologist and synthesis architect George Gaylord Simpson. Smith in turn would serve as a reader, and at one low point, a critical morale booster for Simpson during the time he was writing Life, his breakthrough 1957 college biology textbook.

And between 1959 and 1961, Smith served on the steering committee of the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS), the group credited for “reintroducing” the topic of evolution in its three 1963 textbooks, the Yellow, Blue, and Green Versions. Ironically, it was a BSCS textbook, the Yellow Version, also published by Harcourt, Brace, and World, which supplanted Smith’s work, though Exploring Biology remained in use in classrooms into the 1970s.

Smith’s impressive achievements, though noted in passing by several scholars (Miller, 1966; Grabiner and Miller, 1974; Skoog, 1979), have never received the attention they deserve. Perhaps this is because Smith’s work does not fit well with a conventional narrative, popular since the mid-1970s, that textbooks published after the Scopes trial of 1925 became progressively “less scientific” as authors and publishers capitulated to complaints by fundamentalist Christians and other conservative cultural forces and progressively eliminated references to evolution and other controversial topics. This narrative suggests that textbooks published between 1926 and 1963 do not reflect then current science, or perhaps more importantly, the social views of scientists.

A thorough discussion of this topic can be found in the article “Ella Thea Smith and the Lost History of American High School Biology Textbooks,” published in the 9.08 edition of the Journal of the History of Biology. Also see the compiled list of minor errors discovered in the article by the author subsequent to publication and their corrections.

bn9ryj

iqkc7f

8ca015

t3vl4i

e3nybd