October 23, 2011

MAD magazine was a rare treat when I was a young teenager, a little expensive and difficult to acquire on a regular basis, but a standard newsstand pickup ahead of road trips and summer weeks away. At the time, the late 1960s and early 1970s, MAD was hitting its highest circulation numbers. Yet its humor always felt weirdly out of step, recycled, even a bit reactionary. Of course that’s partially why I liked it. It was creepy anthropology, a moist record of the guilty id of my older siblings and younger aunts and uncles, subversive if a little toothless.

MAD magazine was a rare treat when I was a young teenager, a little expensive and difficult to acquire on a regular basis, but a standard newsstand pickup ahead of road trips and summer weeks away. At the time, the late 1960s and early 1970s, MAD was hitting its highest circulation numbers. Yet its humor always felt weirdly out of step, recycled, even a bit reactionary. Of course that’s partially why I liked it. It was creepy anthropology, a moist record of the guilty id of my older siblings and younger aunts and uncles, subversive if a little toothless.

The magazine had its culturally relevant bits, like Don Martin’s ononmonpidic explosions and Sergio Aragones’ slapstick marginals, but on balance MAD was weighed down by filler of a sensibility that went out with Eisenhower.

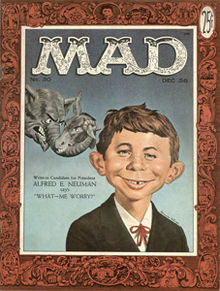

Then there was Alfred E. Neuman.

I never much identified with MAD’s jug eared, gap toothed, ur-teenager. Whether dressed as Marharishi Mahesh Yogi, Indiana Jones or Barack Obama, Neuman seemed to be stuck in a parallel universe where there was never a civil rights movement or a sexual revolution. By high school I had turned to B. Kliban and National Lampoon for social commentary and comic kicks. My interest in MAD moldered.

So it was a real “duh-oh” moment when I read in David Hajdu’s The Ten-Cent Plague that MAD artist Harvey Kurtzman claimed his inspiration for Alfred E. Neuman “was a face from an old high school biology textbook, used as an example of a person who lacked iodine.” With several articles about the connection between popular culture and the “monsters” of biology, how could I have missed such a clear and obvious thing?

Time to dive into another muddy history.

MAD-ologists clog the Internet with origin stories for the Neuman image. Kurtzman himself told several tales, stating elsewhere that he spotted his source on a postcard pinned to an office bulletin board. That story is probably closer to the truth.

MAD-ologists clog the Internet with origin stories for the Neuman image. Kurtzman himself told several tales, stating elsewhere that he spotted his source on a postcard pinned to an office bulletin board. That story is probably closer to the truth.  The big surprise for me was to learn that the image now universally known as Alfred E. Neuman was far from original to MAD. In fact it had appeared throughout the twentieth century, often in association with variations of the phrase “Me worry?”, on postcards, print ads, calendars, business cards, enamel signs, buttons and perhaps even the nose of a World War II-era B-26 bomber.

The big surprise for me was to learn that the image now universally known as Alfred E. Neuman was far from original to MAD. In fact it had appeared throughout the twentieth century, often in association with variations of the phrase “Me worry?”, on postcards, print ads, calendars, business cards, enamel signs, buttons and perhaps even the nose of a World War II-era B-26 bomber.

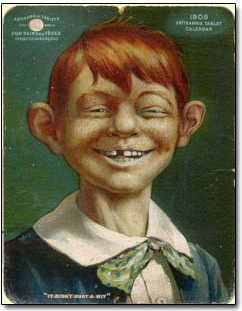

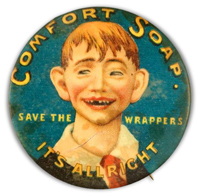

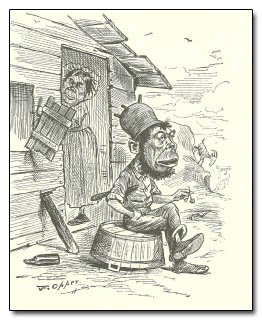

The modern Neuman is said to descend directly from the image of an Irish “simpleton” used in promotions for painless dentistry as well as in advertisements for soap,  baked goods, and other consumer goods and services around the turn of the century (for a complete survey see John Adcock’s excellent article at his blog Yesterday’s Papers). This image in turn was a “made safe” version of the ape-like caricatures of the Irish common a century before (see Jacopo della Quercia’s “Seven Memes …”). This proto-Neuman’s commercial and sociological utility seems to have been similar to that of the “mammy” and “sambo” images still present on our supermarket shelves in the form of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, an endorsement that revealed a product’s basic and uncomplicated pleasures while allowing purchasers, at least white not-Irish purchasers, to reinforce a comforting racial hierarchy with every nickel they spent.

baked goods, and other consumer goods and services around the turn of the century (for a complete survey see John Adcock’s excellent article at his blog Yesterday’s Papers). This image in turn was a “made safe” version of the ape-like caricatures of the Irish common a century before (see Jacopo della Quercia’s “Seven Memes …”). This proto-Neuman’s commercial and sociological utility seems to have been similar to that of the “mammy” and “sambo” images still present on our supermarket shelves in the form of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, an endorsement that revealed a product’s basic and uncomplicated pleasures while allowing purchasers, at least white not-Irish purchasers, to reinforce a comforting racial hierarchy with every nickel they spent.

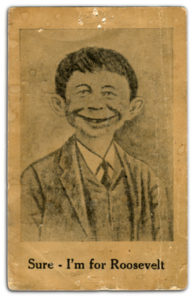

However, unlike its black cousins, the proto-Neuman image lost most of its obvious racial characteristics, its Irish-ness, after World War I. This was probably driven in part by the simple fact that red hair required a two color print job. But likely it was also influenced by the fact that the Irish were becoming “white.” Regardless, the proto-Neuman morphed into a more pan-cultural symbol of obliviousness, its physical characteristics more class than racially centered. The narrowing and misalignment of the eyes became much more pronounced and the grin much more clown-like (though the freckles remained). Locked up with the phrase “Me worry?”, the proto-Neuman image, in both male and female forms, appeared on souvenir postcards produced perhaps as early as 1920 and certainly by the 1930s, opaque in meaning but maybe a fad akin to troll dolls. Later, this proto-Neuman image was enlisted to a more obvious end in the campaign to undermine support for Franklin Roosevelt and his administration’s policies.

However, unlike its black cousins, the proto-Neuman image lost most of its obvious racial characteristics, its Irish-ness, after World War I. This was probably driven in part by the simple fact that red hair required a two color print job. But likely it was also influenced by the fact that the Irish were becoming “white.” Regardless, the proto-Neuman morphed into a more pan-cultural symbol of obliviousness, its physical characteristics more class than racially centered. The narrowing and misalignment of the eyes became much more pronounced and the grin much more clown-like (though the freckles remained). Locked up with the phrase “Me worry?”, the proto-Neuman image, in both male and female forms, appeared on souvenir postcards produced perhaps as early as 1920 and certainly by the 1930s, opaque in meaning but maybe a fad akin to troll dolls. Later, this proto-Neuman image was enlisted to a more obvious end in the campaign to undermine support for Franklin Roosevelt and his administration’s policies.

The “I.M.A.SIMP” button (pictured left) sold at auction in 2010 for slightly more than $2,000. The postcard above cost me $20.

Buttons and postcards were produced that dropped “Me worry?” in favor of “Sure! I’m for the New Deal” and “Sure – I’m for Roosevelt,” with the implication that only an “idiot” could support the Democrat and that the recipient better get out and vote because idiots surely would.

So what of Kurtzman’s claim that the face of a person who lacked iodine inspired his rendering of Alfred E. Neuman? It’s unlikely, as the facial features of “cretins,” as they were generally identified,

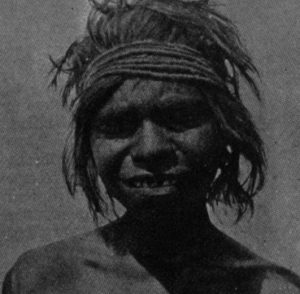

This Neumanesque image was derisively captioned “An Australian feminine beauty” in M. W. de Laubenfels 1949 (1940) biology textbook, Life Science (see related article).

do not map to Neuman’s. However, images of other “deficient” people commonly pictured in old high school biology textbooks could certainly have provided inspiration, if only indirectly.

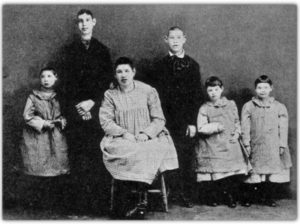

Human anxieties breed monsters, and it is through stories we prepare a defense. But it was not only through comics and horror movies that mid-century Americans practiced confrontation. They also prepared through classroom study. Microcephalics, dwarfs, cavemen, evolutionary throwbacks and genetic degenerates populated the pages of high school and college textbooks. The typical text provided tales of terror every bit as explicit and gruesome as the rags society’s censors were trying to clear off the streets. But the rhetorical goal was far more conservative. Concerns regarding both status and sales meant textbook authors were rather more likely to reinforce the status quo through the claim that existing social relationships reflected relative genetic worth

Identified in Curtis, Caldwell and Sherman’s Everyday Biology (1934, 1943) as “Six feeble-minded members of one family.

than challenge prejudices as scientifically unsound.

The more important driver of social change it turns out was not the biology textbook, but the comic hidden behind its open pages.

But how exactly did the Neuman image work?

In post World War II America, with Fascism vanquished, suburbs sprouting and consumer goods rolling off assembly lines at rates never seen before seen in history, the power of society’s winners to set the rules had rarely been more absolute. Somehow, instinctively and subversively, teenagers took to comics for defense, identifying with the ghoul, the psychopath and the half-wit, Alfred E. Neuman most ironically and iconically. A little later they would take to rock and roll. Embracing the ugly and the underclass, 50’s teenagers picked up a thread established a generation before and paced their parents and teachers toward a place where difference doesn’t diverge from normal, it defines it.

But since there is really no finish line, the image lives on.

Both George W. Bush and Barack Obama have been lampooned in Neumanesque caricature, as their political opponents attempt to score points. Meanwhile, the disaffected subvert the claims of both conservatives and progressives through the embrace and celebration of the dress, style and tastes of those the majority call cretins. In any organized society there is a segment who see disorder as the only possible path to liberation. For these subversives, and teenagers everywhere, there will always be an Alfred.

FURTHER READING

Yesterday’s Papers: The Mysteries of Melvin

The Mad Blog Sunday Mailbag, September 25, 2011.

The Al Feldstein Story, Pt. 3: Go Mad,Young Man!

Hi, thanks for the info! I am trying to track down copyright information for the female version postcard, which you believe is dated in the 1920’s or 30’s – would you have any insight on the copyright?

I’ve looked in Wikimedia Commons to see if she is public domain, but couldn’t find her. I suspect she is in the public domain at this point, but not certain.

It’s the image with “Greetings” at the top.

Any direction you could point me in would be appreciated!

Linda,

Sorry, I don’t know if the image is in the public domain. The auction site at the link (just click on Ms. Neuman) might know more.

dzo3gt

p0y02b