January 29, 2011

Cartoon reprinted in “The Population Bomb: Is Voluntary Human Sterilization the Answer” (c. 1961), a pamphlet published by Dixie Cup magnate Hugh Moore.

Prior to World War II, America’s protectors thought the country’s innocence could be guarded at its gates. Citizen biologists saw the nation’s border as kind of cartographic diaphragm, not entirely reliable in individual instances, but adequate to the task of containing the pool of potential breeders.

But conflict had led to contact, and contact had led to fear. Like the physicist’s “gadget,” biology’s “bomb” was conjured to protect the national body from penetration.

The “population bomb” was made as real and scary to school children in the 1960s as the H-bombs that drove them under their desks.

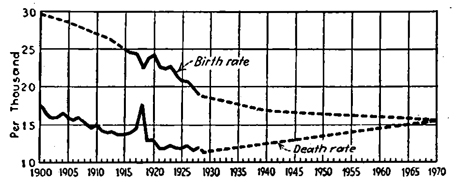

True, from the publication of George W. Hunter’s A Civic Biology in 1914 on, students had been taught that America had a “population problem.” But for the first four decades of the twentieth century, that problem wasn’t runaway growth, it was “differential reproduction.” Pre-war biology textbooks in fact warned that total population would level off by 1970 (see graph below), and when it did, the “quality” of the population would begin to decline if present fertility trends continued. The threat wasn’t one of too many babies. The threat was that too many babies were being born to the ‘wrong’ people – the poor, the criminal, the so-called ‘feeble-minded,’ the swarthy and the black.

As E. E. Stanford fussed in his 1940 biology textbook, Man & the Living World, “Families of professional and business classes of supposedly intellectual rating are not replacing themselves, while those of farmers, laborers, and above all, ‘reliefers’ still maintain increase” (722).

As E. E. Stanford fussed in his 1940 biology textbook, Man & the Living World, “Families of professional and business classes of supposedly intellectual rating are not replacing themselves, while those of farmers, laborers, and above all, ‘reliefers’ still maintain increase” (722).

But by the war’s end, Stanford’s worry was decidedly out of fashion, a quaint relic, a Zeppelin in a jet age.

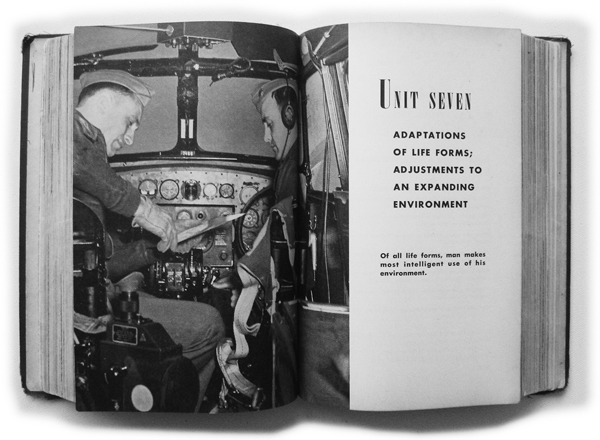

Baker and Mills’ 1943 biology textbook, Dynamic Biology Today, describes the anxieties that bloomed with the airplane and its promise of more fluid mobility. 40 years after the Wright brothers’ first flight, the authors optimistically noted that, “[w]ith rapid expansion in the use of airplanes man will soon obtain a three-dimensional freedom” (484). But this freedom the authors warned would carry a heavy burden. Baker and Mills claimed that the “intelligent people of the world” would have to confront those “slow to accept the benefits of science.” Threats from the “outside” – insects, disease and poverty – could now travel unimpeded through the air, and couldn’t be stopped once in flight. The authors commanded, “we must stamp out disease by eliminating the cause; we must stamp out poverty by eliminating the cause; we must come to recognize the whole world as our immediate environment.”

Before there was a “space age” there was an “air age.” The images above and below-left are from Dynamic Biology Today (1943), by Arthur O. Baker and Lewis H. Mills. The “rapid expansion in the use of airplanes” would, according to the authors, usher in an era of “global living,” where “dissatisfied people living in less productive regions will tend to move to more productive regions.” The authors unselfconsciously identified a few underpopulated and soil rich regions the dissatisfied might move to … in Africa and South America (484).

The post-war realization that the world was intimately interconnected manifested itself in the United States in a call to arms, a get them, or more precisely fix them, before they get us attitude. Suddenly, minor variations between classes seemed trivial relative to the resource sucking threat of the fecund of Africa, India and Puerto Rico. However, any rationalization for a war on reproduction had to address the fact that  flippant disparagement of “inferior” classes, races and genders was no longer acceptable among people who had so proximately confronted the sickening consequences of the casual assumptions of Nordic superiority.

flippant disparagement of “inferior” classes, races and genders was no longer acceptable among people who had so proximately confronted the sickening consequences of the casual assumptions of Nordic superiority.

Alarmists sought an alternate rationalization.

Barely reconstructed eugenicists like Karl Sax led a new generation of apocalyptic writers who, just a decade away from the depleted soils of the Dust Bowl, reconceived the planet as one small, fragile and easily exhausted ecosystem. In an article titled “Population Problems,” which appeared midway through the volume The Science of Man in the World Crisis (1945), Sax repackaged key eugenic arguments in the flimsiest of “race-neutral” containers, and globalized the concern. Though he avoided the word “eugenics” throughout, Sax built his claim on the principle that had animated eugenicists since the turn of the twentieth century: specifically that natural selection’s power to progressively cleanse the species of its weak had been rendered inoperative by advances in medicine and sanitation.

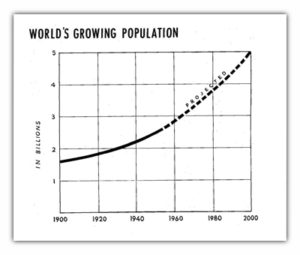

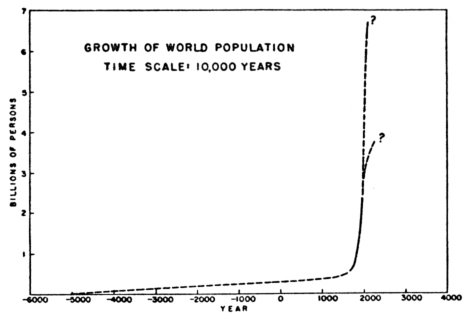

Graph of exponential population growth from Karl Sax’s pamphlet, The Population Explosion, published by the Foreign Policy Association in 1956.

Western industrial societies would have to consciously compensate if they were to prevent civilization from collapsing under the weight of the “morons” who could now survive and breed thanks to the tax dollars devoted to health care and social services.

Sax became heavily involved with population issues in the 1950s. In 1955 he authored the book Standing Room Only, The World’s Exploding Population. It became the basis for a pamphlet published in 1956 by the Foreign Policy Association. Its title would give the world one of two excited phrases that would carry the population control movement through the 1970s – The Population Explosion (see related article).

Sax became heavily involved with population issues in the 1950s. In 1955 he authored the book Standing Room Only, The World’s Exploding Population. It became the basis for a pamphlet published in 1956 by the Foreign Policy Association. Its title would give the world one of two excited phrases that would carry the population control movement through the 1970s – The Population Explosion (see related article).

More influential than the work of Sax were two books published in 1948, William Vogt’s The Road to Survival and Fairfield Osborn’s Our Plundered Planet (see Pierre Desrochers and Christine Hoffbauer’s “The Post War Intellectual Roots of the Population Bomb”). Vogt and Osborn pioneered what later scholars have labeled “neo-Malthusian ecology” (see J. B. Foster’s, “Malthus’ Essay on Population at Age 200: A Marxian View”).

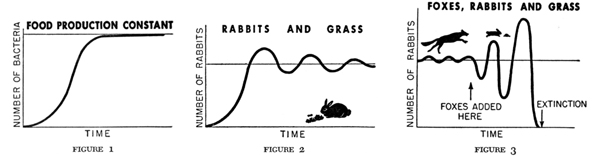

Above: In The Challenge of Man’s Future (1954), Harrison Brown illustrated what he suggested was the “natural” course of evolution. The introduction of a disrupting force (the fox in this case) leads to increasing oscillation in the health and numbers of interdependent species which leads to a spike in growth followed by rapid decline and extinction. This graphic sequence, followed in the text by exponential curves of everything from fossil fuel use to human population growth, illustrated Brown’s theme: if reproduction and resource management were not expertly guided, evolution would soon wipe out humanity.

Despite the best efforts of Sax, Vogt and Osborn, it took some time to completely sever the population control movement’s new ecological frame from its eugenic lineage. In 1954, Harrison Brown, a geochemist who had helped isolate plutonium as part of the Manhattan Project, and who would later edit the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist, published a chilling account of resource exhaustion titled The Challenge of Man’s Future.

Rather than conceptualizing natural selection as a perfecting process that had been subverted by bacteriologists and sewer workers, Brown pictured evolution as an unstable force which, left unmanaged, would drive to extinction the species progressives pictured as its crown. Industrial society, wrote Brown, was an accident of history, and the fight against evolution’s pull would “require effort of a magnitude which transcends all previous human effort” (265). In other words, according to Brown, blind nature, not human effort, had thrown up industry and civilization. People were just along for the ride.

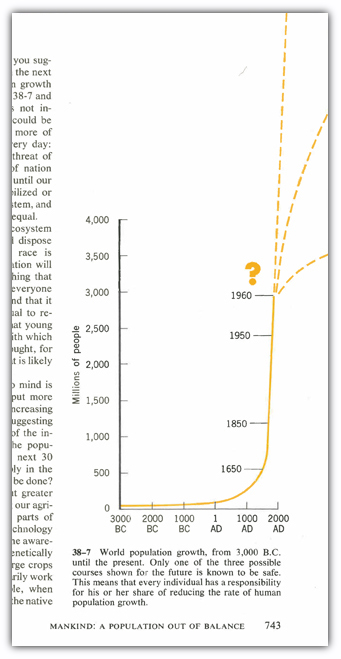

From The Challenge of Man’s Future (1954) by Harrison Brown. The most “explosive” (and as it turns out most accurate) prediction of human population growth to the year 2000. See the UN’s World Population to 2030 for the latest guesses on future trends.

What nature had mindlessly created, Brown thought, it would also mindlessly destroy, unless a few very smart people stepped in and started managing the process. For Brown, rapid population growth was the preface to a period of rapid evolutionary oscillation that would soon shake and destroy civilization. The only thing that might slow the process down would be “a broad eugenics program … that would encourage able and healthy persons to have several offspring and discourage the unfit from breeding at excessive rates” (263).

But Brown, writing in 1954, was among the last science popularizers to speak positively of eugenics, or was at least one of the last to use the word ‘eugenics’ when speaking positively of reproductive management. Growing race, class and (later) gender consciousness, along with a surprisingly slow-to-develop association between the holocaust and eugenics, rendered the word generally unacceptable by the end of the decade (see “The Day Eugenics Died”).

Through the 1950s, no one worked harder than the great naturalist Marston Bates to separate reproductive management from its eugenic roots. His 1955 book, The Prevalence of People, explored the same territory as Brown’s. So closely overlapping were the two texts that Bates, upon reading The Challenge of Man’s Future while his manuscript was in its final stages, “had a horrid feeling that Mr. Brown had already written my book for me.” But Bates, with considerable field experience behind him, was less inclined to the rigid “action-reaction” formulas favored by physicists. Though he considered the 2.5 billion people on the planet in 1950 as probably a billion too many, he had faith in the “plasticity of culture,” and saw hope in its “unpredictability” (249). But the graphs eventually got to Bates as well. His faith in a “natural” solution soon began to oscillate in a Brownian fashion, and would not survive much into the next decade. By the time he wrote the preface to the 1962 reprint of The Prevalence of People, Bates had begun to look admiringly on the progress Japan had seen since implementing its “law of eugenic protection” in 1948.

Opening spread from the original “The Population Bomb,” a 20-page pamphlet that would see an eventual press run of 1.5 million copies by the mid-1960s.

As stated above, eugenics became a dirty word in the later 1950s. Fortunately for the alarmists, it turned out the word wasn’t required to advance the control theme. Hugh Moore, Dixie Cup magnate and pamphleteer, found he could distill the complex arguments of Sax, Vogt, Osborn and Brown down to a simple battle between good and evil, between fullness and hunger, and between freedom and Communism. The argument played well.

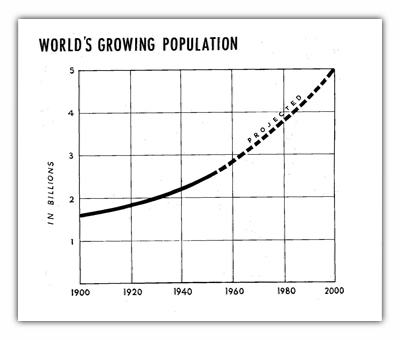

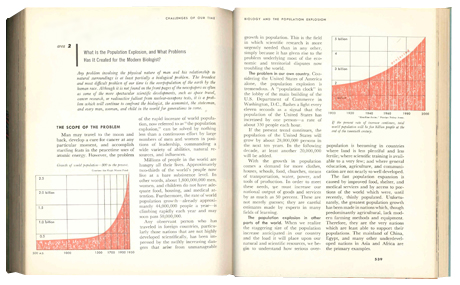

Sax and Moore’s graphs both found a home in the high school textbook New Dynamic Biology, published by Rand McNally in 1959.

Cleansed of its overt racist stench, the exponential curve leapt from the pamphlets of Sax and Moore to the pages of biology textbooks beginning in 1959. Yet all the old tensions remained. People were a cancer, according to Alan Gregg, medical director of the Rockefeller Foundation. And this conceptualization proved popular. But did that mean all people were a cancer? If not, who represented healthy tissue and who the tumor? And who got to decide? Eugenics, a word now unvoiced, remained embedded within the argument over population control.

In the 1960s the exponential curve shot right off the page, climbing faster than the gentle arc of Sax, faster yet than the arc of Moore, to trace almost exactly the rocket-like trajectory illustrated by Brown. An icon of the era, this graph was given its most frightening exposition in Paul Ehrlich’s bestselling 1968 eco-catastrophe, The Population Bomb.

Graph from the 1968 edition of Biological Science: An Inquiry Into Life, more commonly known as the BSCS ‘Yellow Version’.

But then something funny happened. The fuel ran out and, as a Google Ngram of the term “population explosion” so clearly shows, the missile began to fall. A reassessment of progressionist assumptions swept across biology, anthropology, economics and the social sciences in general, driven by a strengthening in the feminist critique pioneered by Mirra Komarovsky and Simone de Beauvoir (see related articles here and here).

In 1994, the Cold War conceptualization of population growth as a crisis that could be managed only by aggressive counterattack, itself came under attack. At that year’s International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, the focus shifted from “bombs” and sterilization to women’s rights and female empowerment. Reintroduced to the debate was the “S-curve,” or the “logistic curve” first advanced by Raymond Pearl in the 1920s (see “A ‘Law of Growth’: The Logistic Curve and Population Control since World War II” by Sabine Hohler). Declining fertility rates suggested a leveling of population growth toward a new normal sometime in the following century. And it was proposed that the motor of that leveling would be increased control by women of their individual wealth and reproductive health.

Today, a few observers worry that the green movement is infected by a neo-eugenic ideology, particularly when it targets the populous poor as a dangerous source of future carbon. They suggest that debate over population control should be erased from the movement’s agenda.

The modern debate is captured no place better than the online journal Climate and Capitalism. Of particular note are the articles and commentary of Betsy Hartmann, director of the Population and Development Program at Hampshire College and author of Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control. She and others in the journal class “Populationism” with racism, classism and sexism as conservative prejudices.

The iconography of human population growth has cycled back to its pre-bomb expression. But the numbers have not changed, only how they are displayed. The consensus view is that human population will top out at slightly fewer than 10 billion people, a number that would have scared the pajamas off of Karl Sax, William Vogt, Fairfield Osborn, Marston Bates and Hugh Moore. But by focusing on growth rate rather than gross numbers, the graph suggests not an explosion, but a quieting, and oddly, an almost sad resignation.

The iconography of human population growth has cycled back to its pre-bomb expression. But the numbers have not changed, only how they are displayed. The consensus view is that human population will top out at slightly fewer than 10 billion people, a number that would have scared the pajamas off of Karl Sax, William Vogt, Fairfield Osborn, Marston Bates and Hugh Moore. But by focusing on growth rate rather than gross numbers, the graph suggests not an explosion, but a quieting, and oddly, an almost sad resignation.

zwf586

8xxv3h

92u6eg