May 11, 2022

Reconstruction was a decade-plus (1863-1877) effort by the U.S. government to manage the readmission to the Union of states that had rebelled during Civil War, with specific demands by Congress to enfranchise and empower the 4,000,000 formerly enslaved people who resided in those states. It succeeded, but only temporarily. Under Federal watch, black men gained the right to vote, and, according to historian Eric Foner, an estimated 2,000 served in public office, including the U.S. Senate, through the nineteenth century. [1] But by 1900, through ongoing campaigns of terror and voter suppression, black Americans in the South were effectively disenfranchised.

Reconstruction was a decade-plus (1863-1877) effort by the U.S. government to manage the readmission to the Union of states that had rebelled during Civil War, with specific demands by Congress to enfranchise and empower the 4,000,000 formerly enslaved people who resided in those states. It succeeded, but only temporarily. Under Federal watch, black men gained the right to vote, and, according to historian Eric Foner, an estimated 2,000 served in public office, including the U.S. Senate, through the nineteenth century. [1] But by 1900, through ongoing campaigns of terror and voter suppression, black Americans in the South were effectively disenfranchised.

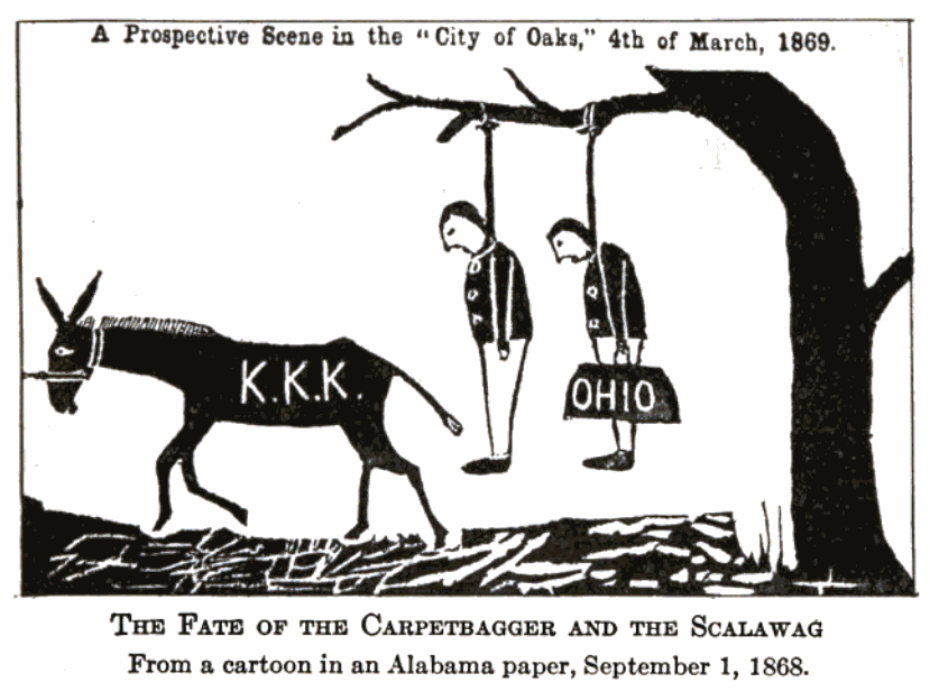

In the decades leading up to and following this disenfranchisement, American history textbooks, academic histories and popular histories constructed a narrative that provided white citizens absolution by positioning Reconstruction as a “tragic era” of “scalawags” and “ignorant negroes” manipulated by invaders from the North, “carpetbaggers,” who “swarmed” South after the Civil War to pillage and humiliate.

This essay traces the development of this “tragic” narrative through a review of American history textbooks published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, focusing on two series: one written by the husband and wife team of Joel Dorman and Esther Baker Steele of Elmira, New York, and a second authored by Susan Pendleton Lee of Richmond, Virginia.

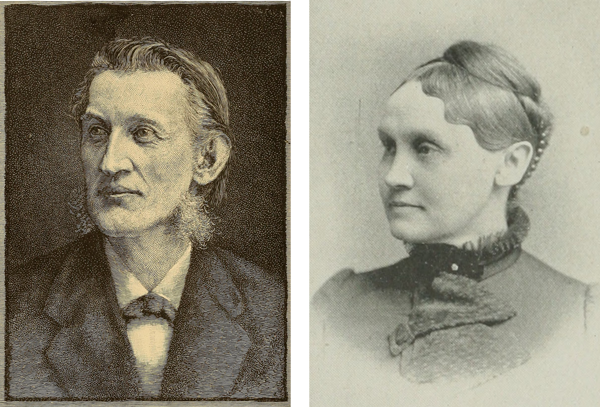

Dorman and Esther Steele: The Dawn of the ‘Carpetbagger’ Narrative

(Joel) Dorman and Esther Baker Steele

Joel Dorman Steele (who preferred the name Dorman Steele) began teaching at 17. He graduated from Genesee College in 1858 (its graduates were later granted alumni status by Syracuse University), and then worked as a school principal. Though described as “frail,” he enlisted and was wounded in the Civil War. After the war, his textbook partnership with Esther Baker Steele proved such a popular and profitable enterprise that the two were able to devote themselves to it fully by 1872, and later serve as major benefactors to both the town of Elmira and to Syracuse University. The Steeles produced and revised some 16 popular high school texts, most under the “Barnes’ Brief History” brand, with Joel taking primary responsibility for the science texts and Esther for the histories. [2] The two traveled extensively, with four trips to Europe, where for months at a time they visited libraries, interviewed educators, and schooled themselves on the latest educational methodologies. Though individual sources are not identified in their books, the authors claimed, “The most reliable authorities have been consulted, recent investigations have been examined, and the ripest fruits of historical research have been carefully gathered.” [3]

The Steele textbook series offered a history of Reconstruction as it was being made. By the 1878 edition of A Popular History of the United States of America, the Steeles were struggling to promote some form of postwar reconciliation acceptable to a national market. To provide such, they adopted a decidedly neutral positioning, a story of Congressional Reconstruction that would prove foundational in later histories. Introducing the term “carpet-bagger” perhaps for the first time in an American history textbook, the Steeles wrote:

The effect of these various congressional measures was largely to exclude from office the better class of the Southern people, and to throw the political power into the hands of an ignorant population, and of Northern men who had gone South after the war. The latter were, in too many cases, mere adventurers – “carpet-baggers,” as they were styled – who had been drawn hither by the hope of position and of plunder (emphasis added). [4]

While offering no celebration of black enfranchisement, in fact only the barest mention of the history of slavery or its end, the Steeles’ text instead focused on symbols of national reconciliation and combined those in a rebirth narrative with symbols of technological progress clearly directed to an assumed white audience. Swarms of bees nesting in a broken drum on “the cannon-plowed slope of Cemetery Ridge” were “storing honey gathered from the flowers on that soil so rich with Union and Confederate blood.” Veterans from both sides “were everywhere to be seen engaged in quiet avocations.” [5] And noted was the “universal amnesty” issued by President Andrew Johnson on Christmas Day in 1868. In association, the authors celebrated the laying, after many failures, of the first successful transatlantic cable in 1866, the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, and the report from the 1870 census that the country’s population, despite an estimated 750,000 battlefield deaths, had grown more than 18% in the preceding decade to 38 million.

In their 1885 textbook, A Brief History of the United States, the Steeles again attempted to promote reconciliation through neutrality. Their goal, according to the book’s introduction, was to “state only those important events in our history which every American citizen should know […and] “[i]n carrying out this idea … avoid all sectional and partisan statements.” [6] But by 1885, the Steeles could not totally avoid discussion of the “bitter and protracted struggles” that had occurred in the establishment of state constitutions under the conditions set by Congressional Reconstruction for readmittance to the Union. In a prominent footnote, they wrote:

As a requisite demanded by Congress for holding office, every candidate was obliged to swear that he had not participated in the secession movement. Since few Southerners could take this “iron-clad oath”, as it was termed, most of the representatives were Northern men who had gone south after the war, and were, therefore, called “carpet-baggers.” [7]

Leaving aside the fact that it is likely that in no case were Northern men (who were not residents of the South prior to the Civil War) the majority of any of the states’ constitutional conventions, there were of course some 2,000,000 Southern men who could have taken the “iron-clad oath,” those formerly enslaved. No mention was made by the Steeles of participation by black men at the conventions. The footnote was amended in 1903 to acknowledge black participation, but also included the following:

Under the rule of these men, in several Southern States, taxes were heavily increased, much public money was spent foolishly or stolen, and the State debts were increased by many millions of dollars for which the people received little or no benefit. [8]

However, in the states of the former Confederacy, there was a market for a history that framed history even less neutrally, that positioned the South as an innocent and largely undeserving victim of punitive and unconstitutional Reconstruction measures.

Susan Pendleton Lee: Rewriting History to Salve Southern Resentments

Susan Pendleton Lee was the daughter of General William Nelson Pendleton, chief of artillery in the Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee. Her husband, Edwin G. Lee, second cousin to Robert E. Lee, was diagnosed with tuberculosis just one year after their marriage in 1859 and would die in 1870.

Susan Pendleton Lee

After, and for 20 years, Lee conducted a private school in Lexington, Virginia. Late in that career she authored a history of Virginia and published the memoirs of her father. Presumably on the strength of those books, in 1891 Lee was recommended to the United Confederate Veterans as a candidate capable of producing “the history of the South, properly, truthfully and impartially written.” [9] That this history would take the form of a textbook was apparently assumed, and Lee produced three, two of which saw further “New” editions, with all lauded by Southern educators. [10]

Unlike the Steeles, Lee listed references at the end of each chapter in her textbooks, noting all under the heading “authorities.” Her section on Reconstruction in the 1896 edition of Lee’s Advanced School History of the United States lists 40 in total. These included a handful of primary sources, specifically the Congressional Record and Reports and Correspondence in Government War Records and a number academic and popular histories, including Woodrow Wilson’s Division and Reunion. But Lee’s dominant sources were hagiographies and personal memoirs of Southern political and military leaders, including Lee’s own Memoir of General Pendleton, by his Daughter.

Like the Steeles, Lee framed her history as a neutral study, just one written from a Southern point of view. She wrote:

Most of the School Histories now in use tell in detail the story of the northern half of the country, while only a few chapters are devoted to its southern half. In this book, an honest effort is made to speak truthfully of both without sectional passion or prejudice. [11]

Further, she hoped her book would “commend itself especially well to the Southern public, while exciting no prejudice, nor eliciting harsh criticism from Northern readers.” [12]

Lee claimed her history, particularly as it related to slavery in the South, was in part simply a story of labor – its evolution in the Americas and its inevitability under capitalism – and the consequences of its sudden abolition. She wrote:

… like every other condition of life, slavery had its evils; but [Southerners] believed that these were less than the ills which would result from its sudden abolition, and they held above all things that they alone had the right to deal with the subject in their own borders, and that the non-slaveholding States had no business to control or coerce them into what was foreign to their opinions and their interests. [13]

However, positional disclaimers, scholarly appurtenances, and claimed sensitivity to the labor question aside, to Lee, Reconstruction was primarily a vindictive assault by extra-constitutional Northerners on the white South. Efforts at black enfranchisement, according to the author, were merely a pretense, a means to political power and exploitation. Describing so-called “carpet-baggers,” Lee wrote, “a crowd of lawless, unprincipled adventurers from the North swarmed down into the Southern States for the purpose of plunder and self-aggrandizement … [only] pretending great love and sympathy for the negroes.” [14] It was unthinkable to the author that black people could possibly be considered by Northerners (or their “scalawag” allies in the South) as fully human. Black voters “were led like sheep by Republican emissaries.” [15] Any defense of the humanness of black people, and certainly any demonstration of humanness by blacks themselves, was dismissed as mimicry elicited and controlled by their new masters, the Military Governors, officials of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and directors of The Loyal Leagues, the last of which, in consort with the Freedmen’s Bureau, were accused of “inciting the negroes to manifestations of hostility, and under their influence outrages were committed too horrible to be described.” [16]

What emerged from this marketplace battle between a somewhat neutral and generally conciliatory presentation of Reconstruction common to Northern writers and exemplified in the work of the Steeles, and the combative, and by any present standard dismissively racist, narrative of Southern writers, particularly Lee, was a common textbook narrative that leaned heavily toward the latter.

Textbook History – The Real Tragedy

In 1926, in his high school textbook History of the United States, published out of New York by The Macmillan Company, author Henry William Elson wrote of the Reconstruction era:

The governments set up during those days were scandalous beyond precedent. The old political leaders were not yet permitted to take part in the state governments. The newly enfranchised freemen were utterly unfit to take the lead, and the result was that a class of unscrupulous adventurers from the North, packing up their goods in a carpetbag, as it was said, went to the South, won the negro voters by their blandishments, and soon had the state governments under their control. [17]

In a gratuitous footnote, Elson added:

The ignorance of great numbers of the negroes was truly pathetic. Many of them were astonished to discover that they would still be obliged to work for a living; misled by northern whites, great numbers wandered about expecting the government to give each family “forty acres and a mule.” [18]

Assuming American history textbooks of any period within the era of compulsory public education represent a consensus view, by 1900, the view held was that black Americans had no claim to the franchise not granted by white Americans. Their opinions and actions were entirely reactive, at best they were accomplished mimics, at worst, a corrosive threat to “civilization,” their “contributions” entirely negative, and their voice not worthy of consideration, or even acknowledgement.

Footnotes

[1] See: Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Perennial Classics), 2014.

[2] The Steeles’ Brief History of the United States sold more than 250,000 copies in 1886 alone. For biographical and other details, see: Anna Campbell Palmer, Joel Dorman Steele, Teacher and Author (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1900); and James Sleeth, “Biography of Joel Dorman Steele,” Chemung County Library District, http://www.ccld.lib.ny.us/steelbio.htm, accessed May 4, 2022.

[3] Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele, A Popular History of the United States of America (New York: A. S. Barnes & Company), 1878, 6. The Steele’s textbooks were often credited only to Dorman Steele or no author at all, as was the case with A Popular History. This essay adopts the position, supported by biographical information, that, at least relative to the history textbooks in the series, the textbooks were co-written by Dorman and Esther Steele.

[4] Ibid, 606.

[5] Ibid, 608.

[6] Steele, Joel Dorman and Esther Baker Steele, A Brief History of the United States (New York: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1885), Preface.

[7] Ibid, 284.

[8] Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele, Barnes’s School History of the United States (New York: American Book Company, 1914), 315.

[9] United Confederate Veterans, Proceeding of the Convention for Organization, and Adoption of the Constitution of the United Confederate Veterans (New Orleans: Hopkins’ Printing Office, 1891), 35.

[10] See for example: “Books and Magazines” in Southwestern School Journal 4:1 (1898), 20.

[11] Susan Pendleton Lee, A School History of the United States (Richmond, VA: B. F. Johnson Publishing Company, 1895), Preface.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid, 279.

[14] Ibid, 546.

[15] Ibid, 548.

[16] Ibid, 550-51.

[17] Henry William Elson, History of the United States (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1926), 765.

[18] Ibid.

References

Du Bois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction in America, 1866-1880. New York: The Free Press, 1998 (1935).

Dunning, William Archibald. Reconstruction: Political and Economic, 1885-1877. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1907.

Elson, Henry William. History of the United States. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1926.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper Perennial Classics, 2014 (1988).

Lee, Susan Pendleton. A School History of the United States. Richmond, VA: B. F. Johnson Publishing Company, 1895.

–. New School History of the United States. Richmond, VA: B. F. Johnson Publishing Company, 1895.

Steele, Joel Dorman and Esther Baker Steele. A Popular History of the United States of America. New York: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1878 (1875).

–. A Brief History of the United States. New York: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1885 (1880, 1879, 1871).

–. Barnes’s School History of the United States. New York: American Book Company, 1914 (1913, 1903).

United Confederate Veterans. Proceeding of the Convention for Organization, and Adoption of the Constitution of the United Confederate Veterans. New Orleans: Hopkins’ Printing Office, 1891.

0rex9a

pvskgg

4te6hq

ey3x0l

fpdd6c

4jndem