Discovered! Ella Thea Smith’s First Textbook

Downloadable PDF of Ella Thea Smith’s 1932 mimeographed and hand bound textbook.

Downloadable PDF of Ella Thea Smith’s 1932 mimeographed and hand bound textbook.

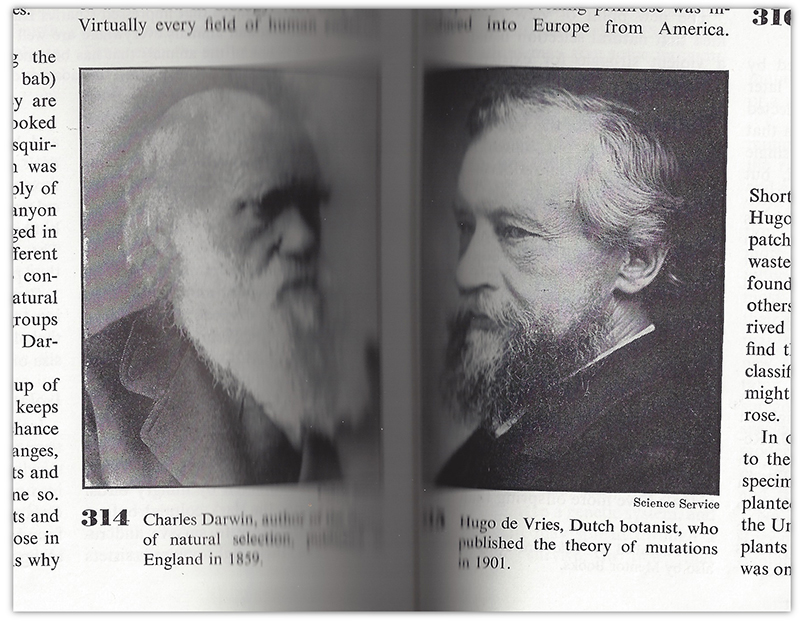

Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries gained global fame in the first decades of the twentieth century for being the guy who finally figured out how evolution worked. Today he is all but forgotten. Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries gained global fame in the first decades of the twentieth century for being the guy who finally figured out how evolution worked. Today he is all but forgotten. Should he stay that way? Or are their good reasons to remember “dead end” scientific theories and the people who loved them?

August 7, 2011 During the first decades of the twentieth century, WASP elites in the U.S. got themselves into quite a tizzy about sex and race. Metaphysical threats, like the death of “virgin forests,” the “darkening tide” of immigration and the dreaded “white plague” of Tuberculosis, combined with economic threats, like the new permanent income…

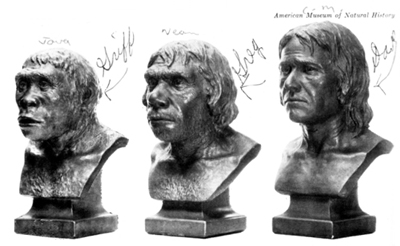

The sculpted busts of “early man” by J. H. McGregor, and the paintings of Neanderthal flint workers and Cro-Magnon artists by Charles R. Knight, alchemized imaginary beasts of centuries past into icons of progress that carried the imprimatur of science. But the narrative they supported was conflicted from the start. Created between the years 1915 and 1920 under the guidance of Henry Fairfield Osborn, director of the American Museum of Natural History, the images were designed to both celebrate scientific progress and alert visitors to the museum’s “Hall of the Age of Man” of an impending eugenic crisis. Osborn believed humans had reached an evolutionary peak in the caves of Lascaux, but that racial mixing was threatening to drag the species back.

It was a downer of story, and the visiting public, or at least the white public, happily skipped past it. Instead they saw in Knight and McGregor’s images visual confirmation of their own racial, cultural and scientific superiority.

Revised 14 February 2010 It is hard to deny that Haeckel’s embryos are an “icon of evolution,” true even if “icon” now evokes Jonathan Wells’ “travesty” of a book (see Matzke). The embryos were reproduced in a majority of high school and college biology textbooks from the mid-1930s through at least the 1960s (See table).…

November 29, 2009 In the 1950s and 1960s, Moon, Mann and Otto’s Modern Biology was the most popular high school biology textbook in the country, commanding upwards of 50% of the market. It was also among the most retrograde and out of date. Scholars have criticized the book for its weak presentation of the topic…

August 8, 2009 The 1930s were a time of remarkable innovation in the development of high school biology. As the subject grew in popularity to become the standard 10th grade science in the United States, textbook authors and publishers, in a wild race to define the curriculum and carve out market share, introduced new organizational…

May 26, 2009 Biology textbook authors in the first decades of the twentieth century, exploiting cultural anxieties fanned by Madison Grant, Henry Fairfield Osborn, Paul Popenoe and other eugenic theorists, helped undercut democracy and shore up the status quo by “confirming” suspicions that the “strongest” weren’t breeding, the “weakest” weren’t dying and that workers who…

May 12, 2009 James M. Reid, an editor at Harcourt Brace from 1924 to 1960, played a crucial role in the history of biology textbooks in the United States. In his 1969 autobiography, An Adventure in Textbooks, Reid discussed how he helped Ella Thea Smith bring her homemade textbook, complete with its thorough discussion of…

March 22, 2009 Ella Thea Smith was the author of the second most popular high school biology textbook in the United States in the 1950s, Exploring Biology. At the height of its popularity it commanded roughly 25% of the market. Exploring Biology was first published in 1938, and was revised in 1943, ’49, ’54, ’59…