Biology and Ballroom Supremacy

AS OF THIS WRITING, the storied East Wing of the White House is 10 days demolished. Without reviews or permissions, President Donald Trump ordered the demolition to make way for a 90,000 square foot gilded ballroom. To many, this action, taken without consultation or the permission of any authorizing agency, felt like a physical assault. Most criticism has been directed toward its Versailles-by-Hobby-Lobby interior, a gold-encrusted space intended for little else but to impress a rotating list of 999 high-rolling guests, who will then be impressed to pay tribute to the ballroom’s master. But let’s not let the interior’s tackiness, or its intent as a grift machine, distract us from the addition’s completely out-of-scale Imperial Rome-inspired exterior, for it is the exterior that provides a good example of how Trump and his minions so generously apply the lube of racism to allow the administration’s con to slide.

How is the exterior racist? In a word, eugenics, an ideology spawned at the end of the nineteenth century, nurtured in the first decades of the twentieth, and on full display in biology textbooks into the 1970s.

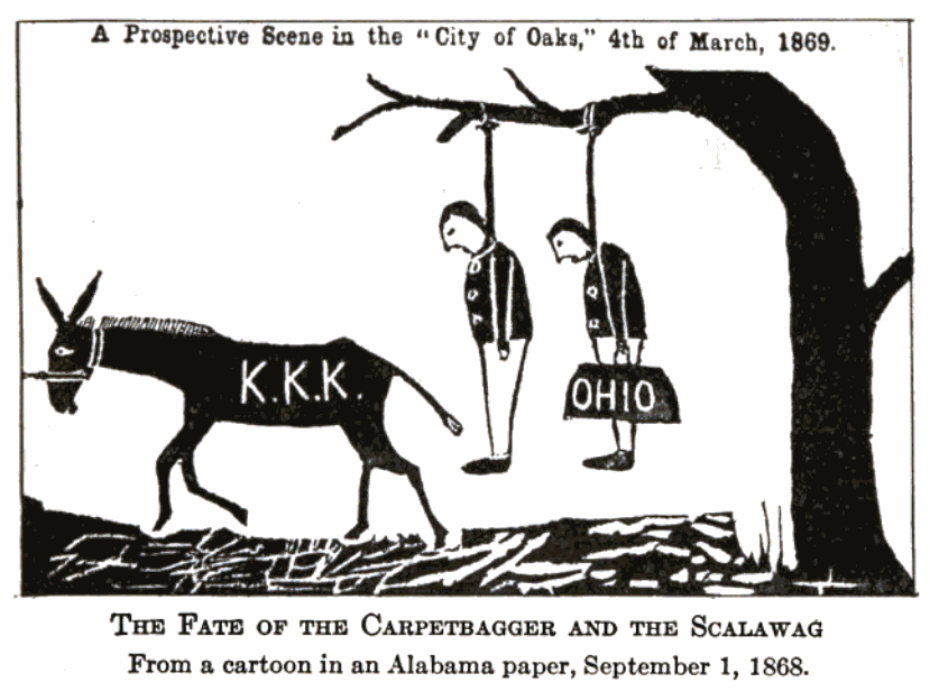

Reconstruction was a decade-plus (1863-1877) effort by the U.S. government to manage the readmission to the Union of states that had rebelled during the Civil War, with specific demands by Congress to enfranchise and empower the 4,000,000 formerly enslaved people who resided in those states. It succeeded, but only temporarily.

Reconstruction was a decade-plus (1863-1877) effort by the U.S. government to manage the readmission to the Union of states that had rebelled during the Civil War, with specific demands by Congress to enfranchise and empower the 4,000,000 formerly enslaved people who resided in those states. It succeeded, but only temporarily. Evidently, the “new” cause of tech millionaires and billionaires like Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, and Elon Musk is the survival of our species, at any cost, until it reaches a “transhuman” plane. Once reached, humans, or I guess post-humans, will push out into the universe physically and virtually for the next 10e100 years, and perhaps beyond.

Evidently, the “new” cause of tech millionaires and billionaires like Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, and Elon Musk is the survival of our species, at any cost, until it reaches a “transhuman” plane. Once reached, humans, or I guess post-humans, will push out into the universe physically and virtually for the next 10e100 years, and perhaps beyond.

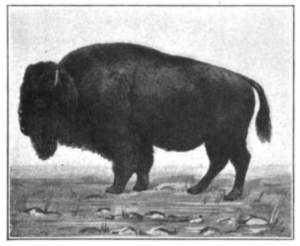

To our Rachel Carson-tuned ears, the word conservation means allowing nature to hold sway, to designate areas as wetlands, protected habitats, and forever wild, to be humble and accept that nature is usually smarter than we are. But to biology textbook authors in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, influenced by the eugenic ideas of Henry Fairfield Osborn, Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevel,t and others, conservation meant something else entirely. It meant, first, preserving select symbols of American virility, like the redwood tree, the bison, and most importantly, their own “great race,” and second, managing the rest of nature – forests, water resources, wildlife, and soil – so that it could be exploited maximally without collapse.

To our Rachel Carson-tuned ears, the word conservation means allowing nature to hold sway, to designate areas as wetlands, protected habitats, and forever wild, to be humble and accept that nature is usually smarter than we are. But to biology textbook authors in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, influenced by the eugenic ideas of Henry Fairfield Osborn, Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevel,t and others, conservation meant something else entirely. It meant, first, preserving select symbols of American virility, like the redwood tree, the bison, and most importantly, their own “great race,” and second, managing the rest of nature – forests, water resources, wildlife, and soil – so that it could be exploited maximally without collapse.