February 10, 2010

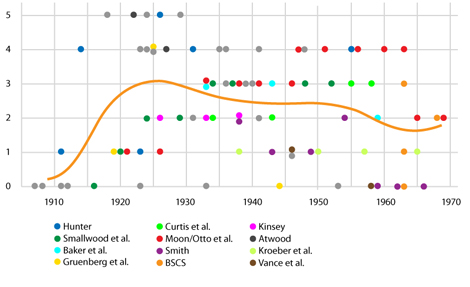

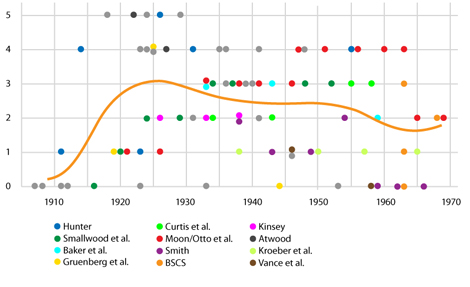

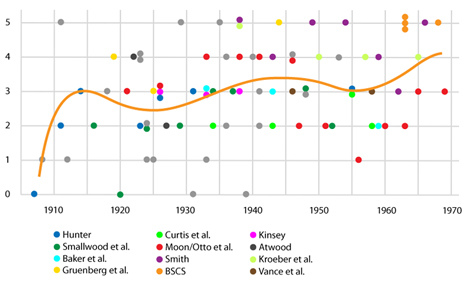

The chart below tracks the relative priority of the topic of eugenics in the American high school biology curriculum. It is based on review of 80 textbooks published between 1907 and 1969. Though there are exceptions, as a rule, textbooks first published in the years prior to 1938 were generally more eugenic than average in their later editions, and textbooks published from 1938 on were generally less eugenic than average in their later editions. Further, with the exception of Moon (first published in 1921), only the less eugenic Smith and Kroeber and Wolff texts survived into the 1960s.

A couple of additional observations:

Scopes: As the chart indicates, the Scopes-era anti-evolution movement in the United States correlated with the peak of eugenic fervor in American biology textbooks. However, the movement was indiscriminate. Any textbook that contained an explicit mention of human evolution, whether that particular text promoted eugenics or not, was subject to censorship – from the most harshly eugenic, like William Atwood’s 1922 Civic and Economic Biology, to the sweet, like Gilbert Trafton’s wonderful 1923 Biology of Home and Community. The latter, though it featured no eugenic language, generated controversy in North Carolina. Despite after the fact claims from creationists, eugenics does not seem to have concerned early fundamentalists.

The Rise of Nazism and World War II: Though Raymond Pearl criticized eugenics as far back as 1927, and the Nazi application of harsh negative eugenic measures pushed liberal scientists like Julian Huxley and Hermann Muller to frame a softer reform eugenics in the mid-1930s, the data demonstrate no sharp drop in the presentation of the topic through the 30s, 40s and 50s, only a gradual decline. This supports Wendy Kline’s claim from Building a Better Race (2001) that the eugenics movement was not “weak and discredited after 1930,” as many scholars contend, but had worked its way deeply into the popular consciousness.

Evolution vs. Eugenics: Though the topics of evolution and eugenics were tightly wed in the economic and civic biologies published from 1914 through the latter 1920s, textbooks with the strongest and most up to date presentation of evolution (Smith, Kroeber and Wolff) were significantly less eugenic than popular textbooks with poorer evolutionary content (Smallwood, Curtis and particularly Moon).

Moon: As with the data tracking the relative priority of the topic of evolution (see chart), the popular Moon text skews the results (see related article). Combined, the data suggest that though conservative regions of the country may have taken issue with the teaching of the topic of evolution, the teaching of eugenics, which discouraged mating across race and class lines, was less controversial.

See – Database: Eugenics in High School Biology Textbooks

Where other textbook authors focused on the history of vertebrates culminating with human dominance, Kinsey focused on the behavior of insects culminating with balance in nature.

Where other textbook authors focused on the history of vertebrates culminating with human dominance, Kinsey focused on the behavior of insects culminating with balance in nature.

Scholars have criticized the book for its weak presentation of the topic of evolution. The 1956 edition is the focus of particular scorn. In that edition all references to human evolution were deleted. The publisher of the second most popular textbook, Exploring Biology, followed suit a few years later.

Scholars have criticized the book for its weak presentation of the topic of evolution. The 1956 edition is the focus of particular scorn. In that edition all references to human evolution were deleted. The publisher of the second most popular textbook, Exploring Biology, followed suit a few years later.

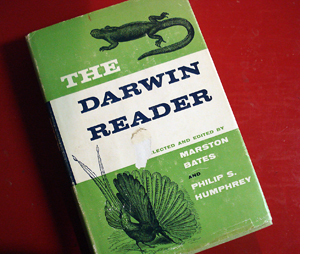

This neat bit of near-ephemera was among the first attempts to restore some of Darwin’s lost luster. Published in 1956, The Darwin Reader was a “best of” (and somewhat sanitized) collection of the writings of Charles Darwin edited by two professors at the University of Michigan, Philip S. Humphrey and Marston Bates. The editors noted that hardly anybody in the mid-1950s was reading Darwin, professionals included. They thought a good digest would help.

This neat bit of near-ephemera was among the first attempts to restore some of Darwin’s lost luster. Published in 1956, The Darwin Reader was a “best of” (and somewhat sanitized) collection of the writings of Charles Darwin edited by two professors at the University of Michigan, Philip S. Humphrey and Marston Bates. The editors noted that hardly anybody in the mid-1950s was reading Darwin, professionals included. They thought a good digest would help.