November 5, 2009

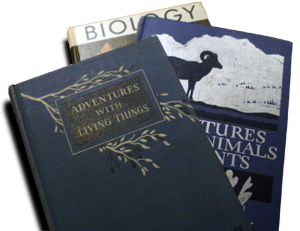

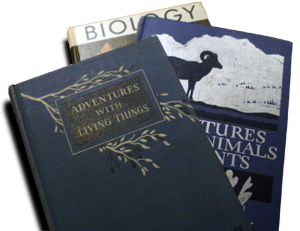

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

Authored by accomplished New York City educators Elsbeth Kroeber and Walter H. Wolff – she the sister of famed anthropologist Alfred Kroeber and he an intellectually ambitious department chair at DeWitt Clinton High School – Adventures (1938) delivered a solid corrective to the grossly anthropomorphic and depressingly deterministic textbooks of the 20s and 30s. It was one of the first of a wave of biology textbooks authored during the “Nazi years” that actively countered class and race prejudice and worked to undercut popular and institutional enthusiasm for eugenics. Other notable texts of this ilk include Smith’s Exploring Biology (also 1938) and Bayles and Burnett’s Biology for Better Living (1941).

ADVENTUROUS INDEED

Kroeber and Wolff’s brave book signaled its attack on the standard narrative and common conceits right from its opening pages.

Instead of the usual run of plants and animals from simplest to complex leading to “man,” the crown of creation and a creature apart, Adventures started with “man,” situated the species firmly within an interdependent biological space, and then moved with haste “down” through 150 pages of apes, reptiles, fishes, insects, invertebrates, to the “invisible” organisms and two brief chapters on plants on its way to the main body of the book, a nearly 500 page unit-based “unity of life” biology.

And as if that wasn’t enough, Kroeber and Wolff closed with another 150 pages on the “great generalizations of biology:” the unity of all living things, balance in nature, geological and organic change, the interplay of heredity and environment, evolution by the accumulation of very small changes, and finally, the potential of science to drive progress.

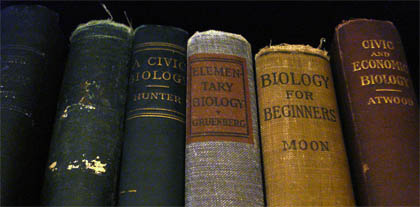

To understand how radical this was one need only compare Adventures With Living Things to the most popular textbooks at that time: Moon’s Biology, Smallwood’s New Biology, Baker and Mills’ Dynamic Biology and Curtis, Caldwell and Sherman’s Biology for Today. None of these texts devoted more than a few dozen pages to the “great generalizations.” All twisted and edited themselves to accommodate the concerns of textbook committees and school boards fearful of community objections to the teaching of reproduction and human evolution. Many contained startling race-based proofs of evolutionary “progress.” And all promoted eugenics without qualification. In fact, Moon’s text, which became Modern Biology in 1947, would continue to promote eugenics, calling it a “young science,” well into the 1960s.

However, Adventures With Living Things never gained much commercial traction. Though it was used in classrooms throughout New York City, no doubt because its authors had some influence there, it appears never to have generated much interest beyond the boroughs.

Why?

discovered that their competitors had gotten the jump on them by publishing “acceptable” alternatives to texts like his and others not yet hip to the latest fundamentalist fashion.

discovered that their competitors had gotten the jump on them by publishing “acceptable” alternatives to texts like his and others not yet hip to the latest fundamentalist fashion.

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

Published in 1938, Adventures With Livings Things was one of the most comprehensive, most far-sighted American high school biology textbooks of the century. It was also one of the most challenging. And in terms of commercial success and influence, perhaps one of the most disappointing.

Amram Scheinfeld’s 1939 You and Heredity was a bestseller, a hit not only with the general public, but also with life scientists. It was rightly lauded as an excellent layperson’s primer on the state-of-the-art in human genetics and heredity, and a serious critique of the racist, nativist and even anti-homosexual sentiments common among early eugenics supporters.

Amram Scheinfeld’s 1939 You and Heredity was a bestseller, a hit not only with the general public, but also with life scientists. It was rightly lauded as an excellent layperson’s primer on the state-of-the-art in human genetics and heredity, and a serious critique of the racist, nativist and even anti-homosexual sentiments common among early eugenics supporters. After authoring

After authoring  In its obituary, the Washington Post described Bentley Glass (1906-2005) as a “peripatetic figure in the 1950s and 1960s,” a man who seemed to be everywhere and advising everyone. In other obituaries Glass was described as “provocative” and “outspoken.” Editors of course made note of Glass’ more controversial comments, such as his 1971 statement that, “No parents will in that future time have the right to burden society with a malformed or mentally incompetent child,” a remark that the New York Times wrote, “is still regularly deplored by opponents of abortion” (Martin, 2005). Other notices, such as the one that appeared in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, labeled Glass more forgivingly as a “rabble-rouser,” and noted, “Of all his pronouncements, none permeated the cultural lexicon more than his 1962 prediction that cockroaches would be the sole survivors of nuclear war” (Bernstein, 2005, p. B6; Erk, 2005, pp. 164-173; Martin, 2005; Anonymous 2005, 14).

In its obituary, the Washington Post described Bentley Glass (1906-2005) as a “peripatetic figure in the 1950s and 1960s,” a man who seemed to be everywhere and advising everyone. In other obituaries Glass was described as “provocative” and “outspoken.” Editors of course made note of Glass’ more controversial comments, such as his 1971 statement that, “No parents will in that future time have the right to burden society with a malformed or mentally incompetent child,” a remark that the New York Times wrote, “is still regularly deplored by opponents of abortion” (Martin, 2005). Other notices, such as the one that appeared in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, labeled Glass more forgivingly as a “rabble-rouser,” and noted, “Of all his pronouncements, none permeated the cultural lexicon more than his 1962 prediction that cockroaches would be the sole survivors of nuclear war” (Bernstein, 2005, p. B6; Erk, 2005, pp. 164-173; Martin, 2005; Anonymous 2005, 14).