The Day Eugenics Died

July 3, 2009

I was not taught much of the history of eugenics in school, but I somehow absorbed that it was an “old” idea, one that had been thoroughly discredited once the horrors of the Nazis were exposed.

So it came as a bit of a surprise to find that many American high school and college biology textbooks continued to discuss eugenics as if it were a non-controversial idea well into the rock-and-roll era. In fact, the most popular textbook published in 1960, Moon, Otto and Towle’s Modern Biology, referred to eugenics as “a young science,” (648) and suggested its methods would surely begin to see application once a few more properly studied human generations had passed.

So it came as a bit of a surprise to find that many American high school and college biology textbooks continued to discuss eugenics as if it were a non-controversial idea well into the rock-and-roll era. In fact, the most popular textbook published in 1960, Moon, Otto and Towle’s Modern Biology, referred to eugenics as “a young science,” (648) and suggested its methods would surely begin to see application once a few more properly studied human generations had passed.

Yes, Modern Biology was always a bit behind the times. But when it came to eugenics, it wasn’t behind by that many years.

Though a few popular textbook authors began to challenge the assumptions of eugenicists starting in the late 1930s (Smith, 1938) and then significantly downplay or drop the topic entirely starting in the 1940s (Gruenberg and Bingham, 1944), most continued to repeat, in only slightly abridged form, the same claims of eugenic necessity and urgency advanced in the 1920s and 1930s.

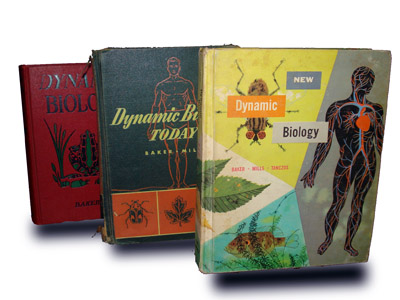

Rand McNally’s Dynamic Biology series – Dynamic Biology (1933), Dynamic Biology Today (1943) and New Dynamic Biology (1959) – provides an illustrative example of the history of the idea of eugenics in American high school textbooks. A comparison of these texts not only demonstrates the continued affection authors held for the idea of eugenics, but, when one looks carefully, hints strongly at what finally forced authors to abandon explicit promotion of the topic.

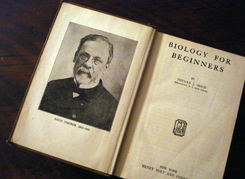

It’s a powerful symbol of capitulation: the straight on, serious portrait of Charles Darwin, the wizened, white bearded author of the Origin of Species and father of modern biology, was stripped from the frontispiece of a popular high school textbook, replaced by, of all things, a cartoon of the human digestive tract. According to New York Times writer Susan Jacoby, the insidious nature of the fundamentalist campaign to censor biology textbooks after the Scopes trial of 1925 is

It’s a powerful symbol of capitulation: the straight on, serious portrait of Charles Darwin, the wizened, white bearded author of the Origin of Species and father of modern biology, was stripped from the frontispiece of a popular high school textbook, replaced by, of all things, a cartoon of the human digestive tract. According to New York Times writer Susan Jacoby, the insidious nature of the fundamentalist campaign to censor biology textbooks after the Scopes trial of 1925 is  First, Moon replaced the portrait of Darwin with a portrait of Louis Pasteur (

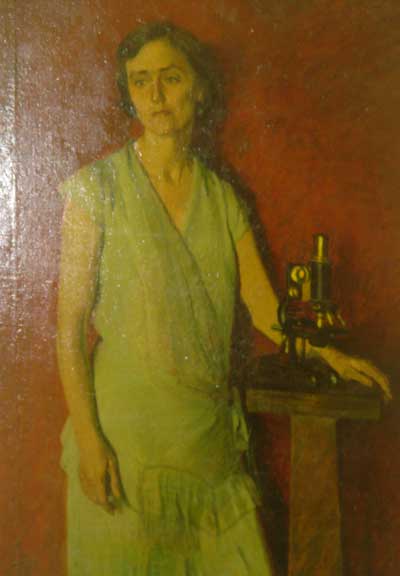

First, Moon replaced the portrait of Darwin with a portrait of Louis Pasteur ( Ella Thea Smith was the author of the second most popular high school biology textbook in the United States in the 1950s, Exploring Biology. At the height of its popularity it commanded roughly 25% of the market. Exploring Biology was first published in 1938, and was revised in 1943, ’49, ’54, ’59 and ’66. It featured many firsts.

Ella Thea Smith was the author of the second most popular high school biology textbook in the United States in the 1950s, Exploring Biology. At the height of its popularity it commanded roughly 25% of the market. Exploring Biology was first published in 1938, and was revised in 1943, ’49, ’54, ’59 and ’66. It featured many firsts.