Updated 30 July 2011

I’d been trying for a couple of months to kick out an article on a curious college biology textbook, The World of Life by Wolfgang F. Pauli (who should not be confused with the more famous physicist, Wolfgang E. Pauli). Published in 1949, The World of Life had long fascinated me, particularly its final unapologetic climax chapter, “Human Genetics and Eugenics” (click image to view). The whole thing just seemed so remarkably wrong; a tortured post-World War II effort to “save” eugenics, as if it were an adorable baby being thrown out with that nasty Nazi bathwater.

But I worried that The World of Life was an exception, a weird one-off a decade or more out of step, not really worth deep examination. Before I could write confidently, I realized I had to know how Pauli’s text fit into the history of college biology education in the twentieth century.

So it was off to AbeBooks (again!), credit card in hand. Before you could say “security code,” I was anticipating the arrival of nearly a dozen book-filled “bubble-lopes.” Fortunately, I didn’t have to wait long to find out I was on to something.

The very first of my new acquisitions, Biology: And Its Relation to Mankind (1949) by A. W. Winchester, told me Pauli’s text was no exception. The subsequent arrival of Biology: The Human Approach (1950 – later titled Biology) by Harvard professor Claude A. Villee, a text which identified feeble-mindedness as “the biggest single eugenic problem” (461), suggested a trend: Contrary to received wisdom, biologists did not drop eugenics like a hot stone after World War II. Instead, as I wrote in a previous article, a few college textbook authors “doubled down and began to defend the ideology with more aggressive rhetoric and moments of near-pornographic spectacle.”

Counter-intuitive. Interesting. Compulsion-triggering.

Now, in addition to 82 American high school biology textbooks, I own or have sourced 38 college-level biology textbooks. Though the college collection is considerably smaller and perhaps not quite as complete and coherent as the high school collection, I am fairly confident it is representative.

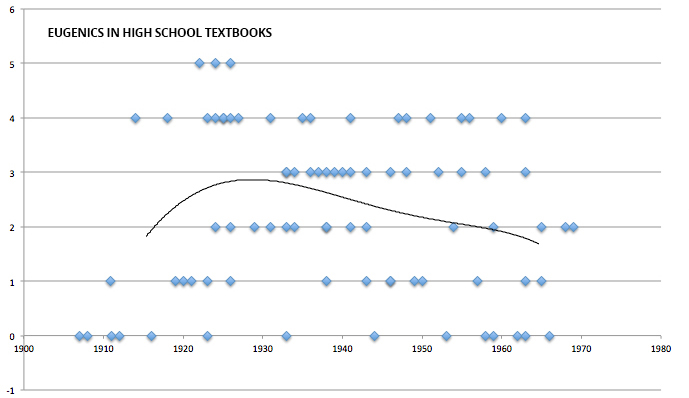

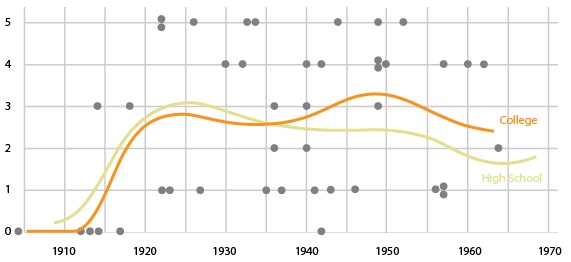

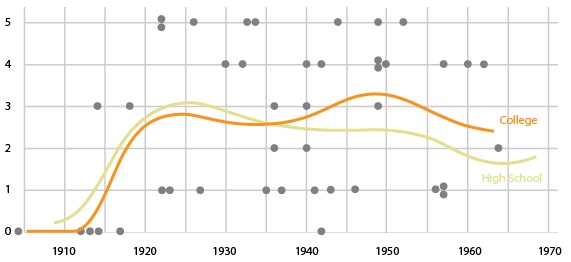

THE RELATIVE PRIORITY OF THE TOPIC OF EUGENICS IN AMERICAN COLLEGE-LEVEL AND HIGH SCHOOL BIOLOGY TEXTBOOKS 1904 – 1964

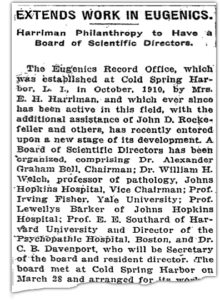

The orange trendline traces the relative priority of the topic of eugenics in American college-level biology textbooks published between 1904 and 1964 (based on the table below).* The yellow trendline traces the relative priority of the topic in high school textbooks published during the same era (see related article). Consistently throughout the twentieth century, college texts were as eugenic as their high school counterparts, with a notable increase in the boldness of their presentation of the topic, both in relative and absolute terms, in the years immediately following World War II.

I hope to add a couple context bullet points and write a few longer articles referencing this collection soon (perhaps on topics other than eugenics, which I admit has sort of taken over Textbook History lately). But I thought I’d get this draft database out there, including my somewhat subjective “Eugenics 0-5” rating. I’ve included links to public domain texts, related articles and available biographical information on authors.

See: Database: Eugenics in College Biology Textbooks

Also see: Eugenics in 20th Century High School Biology Textbooks.

* The chart above reflects a eugenics score of “1” for the popular Foundations of Biology by Lorande Loss Woodruff (see page 297), published in 7 editions through 1946 (though only the 1922 and 1937 editions have been directly reviewed). A score of “2” would not substantially alter the shape of the college trendline, but would amplify it through 1946, thereby decreasing the relative drama of the post-war bump.